RECENTLY I read an article that made me shudder with geekly delight. Japan’s Suidobashi Heavy Industry, a company whose mission aims “to spread human ride robots” around the globe, had developed a real life mechanized suit. Outfitted with groundbreaking V-Sido software allowing the technology to be intuitively piloted by an actual human being in the cockpit, the $2 million prototype’s name had a neo-industrial ring to it: KR01. Like something out of VOTOMS, a Japanese animated television show from the 1980s, the cockpit illuminates with high-tech scanners and movement guidance systems when the human pilot climbs inside. You can check it out in action here. It’s all real. Even the disturbing smile-gun trigger feature and the (let’s hope intentionally) absurd safety segment.

Although I viewed the venture mostly as a remarkable toy being brought to life, the creator of this sophisticated nerd-machine, Wataru Yoshizaki, claimed he actually envisioned a future in which robotic suits, or Mechas as they’re popularly termed, would become purposed for daily life. He spoke of average citizens making mundane trips to the grocery store piloting five-ton mega-robots. Though he had his prototypes equipped with rapid-fire squirt guns and BB pellet Gatling cannons, he did so in the manner of a man establishing a preliminary vision for the future. Machines like his, he explained, are really not all that unusual in the canon of human inventions. They are simply powerful extensions of our bodies comprised of earth’s crude materials.

Though only recently gaining youth popularity in the West, this phenomenon of humans piloting machines in their likeness has been building for a time now in the opposite hemisphere. Branded in the fifties and sixties and popularized in Japanese animation and comics (Manga), giant robot stories were founded, in part, on the backs of giant monsters. Before human-outfitted tanks took to the scene, creatures like Godzilla and Mothra were the first larger-than-life titans to duke it out over major metropolitan cities. In the early days of Toho Co., Ltd., the studio responsible for everything from Godzilla and Rodan to Seven Samurai and Yojimbo, a creature would rise from the depths of the ocean with the sole intention of leveling Tokyo. A highly specialized civilian task force comprised of scientists and elite military personnel would be dispatched to defeat said creature, and that was that. The formula didn’t differ all that much from the American science fiction films of the nineteen forties and fifties such as The War of the Worlds and The Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Human ingenuity, and science in particular, could always be counted on to curtail earth’s destruction. The fact that earth’s destruction was coming in the form of gigantic radioactive beasts was only of limited intrigue.

But in 1958 a new cultural advent was born in Mitsuteru Yokoyama’s 1956 Manga Tetsugin-28-go. By this time, Japanese comics had already taken hold in their societal mainstream, and creative production was in furious stride. The origin of Testugin-28-go, the first notable giant robot series, was similar to that of Japan’s most famous mega-monster, Godzilla, who had been awakened by nuclear radiation. The story followed the final days of World War II, in a reality in which the Japanese military developed a super-weapon to save the empire. This weapon was a three-story-tall, remote controlled robot. It stood just as tall as any world-threatening monster, but as opposed to being spawned in radioactive sludge, was manufactured and controlled by industrious human beings.

That giant robots and giant monsters would eventually meet on the battlefield is hardly surprising. Both phenomena stem directly from the historic trauma wrought upon the world by the introduction of the nuclear age. But at the beginning of their respective runs as genres the two remained epically segregated. Tesugin-28 started out fighting other enemy robots and various criminal enterprises led by a cookie-cutter villain named Professor Shutain Franken. Godzilla started out fighting enemy monsters and/or national armies. But neither came near the other for years, each creation remaining autonomous. Eventually, however, happenstance ignited the inevitable and a new genre emerged, one in which outsized robots would combat outsized monsters. This event would come to be known as the establishment of the ‘Super Robot’ genre, and it would take hold for the long run.

Shows like Mezinger Z, appearing in comics the early nineteen seventies, primed the way for what was to come. Although the giant monsters in Mezinger were mechanized and controlled by an evil genius named Dr. Hell, they were fashioned after hydras and lizard-beasts in the style of Godzilla and Rodan. Getter Robo, a Manga series adapted to animation shortly after Mezinger Z in 1974, took the final plunge. In it a transformable robot piloted by three humans squared off against an ‘Evil Dinosaur Empire.’ These dinosaurs were not scientifically or genealogically akin to anything a paleontologist would find recognizable. Instead they were modeled after Toho cinema monsters, or Kaiju, of the thirties, forties, and fifties. In Getter Robo you could first witness robots and monsters fighting for dominion over earth. Contact had been made.

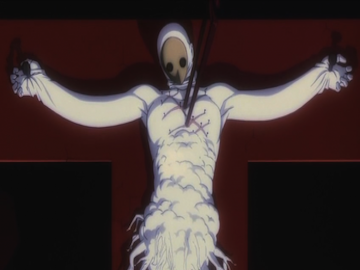

Similar to the manner in which trends in American science fiction were born out of the Cold War, it’s impossible not to consider the Super Robot genre outside of a Japanese cultural context specifically dealing with the horrors of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. But what’s also interesting is that the West has found something worthwhile in the genre as well, to the point where feature films, like Pacific Rim most recently, drive a hardcore fan base. Perhaps this has something to do with the ostentatious scale of these narratives. There’s something simple to embrace in them. Something simple that provides generous fuel for increasingly intellectualized takes on the genre with features like Neon Genesis: Evangelion, a critically acclaimed Super Robot serial, in which faith, psychosis, and humanity are dismantled in a brutal, self-conscious manner. In it, monsters become ‘Angels’ and robots become ‘Evas.’ The world is pummeled into a Freudian potato mash of sexuality, gender, and self. The Super Robot genre in its facile construct is capable of holding quite a lot on its shoulders, it turns out. Monsters represent more than teeth and claws.

Though the word itself has come to mean ‘giant monster’ in western society, a Kaiju by definition is just a word for ‘strange creature’ in Japanese. By that stretch, Swamp Thing or Frankenstein could qualify just as much for the position as Godzilla or Gamera. The word Daikaiju more accurately describes what the West was recently exposed to in Pacific Rim, as it translates to ‘giant strange creature.’ Traditionally, such beasts are modeled after animals. Godzilla himself is a hybrid of the kanji gorira, for gorilla, and kujira, for whale. So whenever you hear that quintessential Godzilla roar (the trademarked sound of a piece of copper being dragged across a stand up base, before being played in reverse), you can know you are truly heralding the forlorn cry of a 300-ton Whale-Gorilla. These creatures are often represented as perversions of nature. They are hybridized, nuclear-ized, galactic mutants that exist as a result of what humans have unleashed upon the world in the modern age. They’re massive, awkward symbols of our most basic fears.

Giant robots by contrast are defined and reinforced by the presence of an enlightened human element. Without us at the helm, these massive metal constructs would be nothing more than fallow hunks of steel. One of the defining tenants of giant robots is that they are navigated from the inside, and in the rare case that they aren’t, they’re remote controlled. Sometimes, depending on the series’ premise, a human can connect with a robot and dictate its actions via voice or telekinetic command, but one thing is always for certain: human beings are leading the charge against doom and chaos. If giant monsters are symbolic of destructive forces war and nuclear technology, then Super Robots are reclamations of that technology for proactive use.

Humans in general have an uneasy relationship to technology. Machinery continues to change our world so rapidly that tracking its daily sociological effects is near impossible. We wrestle with the positive and negative implications of our development, weighing the good of increased efficiency and longevity against the bad of disinformation, laziness, and violence. Whenever I watch/read a good Super Robot story, I feel as if I’m witnessing humanity at war against its own progress. Good technology versus bad technology. Science versus nature. Humans attempting to reconcile evolution with their place in the natural world. When giant monsters erupt like volcanoes and hurricanes to unleash uncertainty and terror I’m reminded of Global Warming, dirty bombs and genocide. When they lay waste to infrastructure without rhyme or reason, punishing us for deeds we should have had the foresight to prevent, I think of sickness, plague, and droughts. Giant monsters remind us that without three hundred foot tall metal suits human beings are small, flimsy, and horribly vulnerable. The giant robot is an answer to the chaotic world we live in. It is a physical manifestation of ingenuity and creativity; an aegis against our own savagery and weakness. It shows us technology is a part of what we are now, and that while we fear it, we must learn to live with it for the long term.

If I had millions of dollars at my disposal, would I buy one of Suidobashi’s Kurata robots? Sure. It’s a geek’s dream come true. But without purpose, a giant machine becomes nothing more than an expensive toy. Perhaps the future will change that. Though hopefully not for the wrong reasons.