“I didn’t know much about the history of art. The development of art. Where things came from. At school, I did this kind of wild, crazy painting. Outside the studio they had these ceramic heads that the pottery department was making—these surrealist, ugly-looking heads on the wall—so I did a painting of all these trees, and each tree was a different color, and the sky was red. To me it was a kind of painting that didn’t look like anything else I had ever made. I wasn’t that experienced with the art world. So when I went into class that day they said, ‘Oh, you’re a fauvist now,’ and I was like, ‘What’s that?’ and they said, ‘a wild beast,’ and I said, ‘I kind of like that’ (laughs), and they said, ‘Yeah. You would.’”

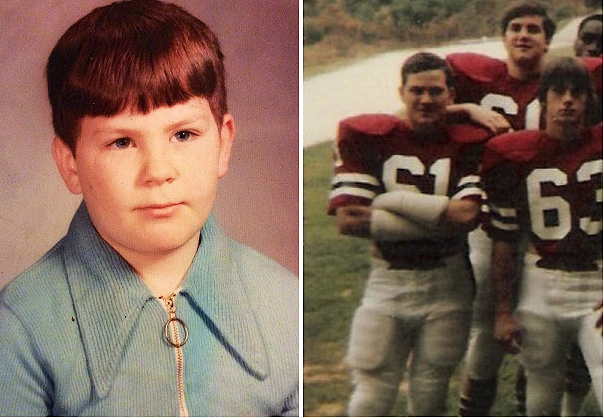

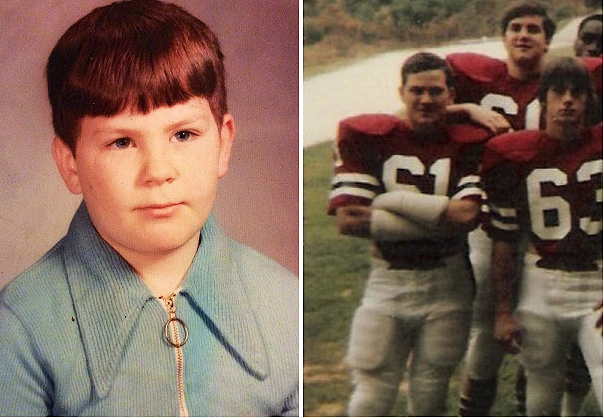

Buchanan: I guess my first love of any art form was music. I listened to the little forty-fives that my mom and dad had, and my sister had. My sister had the Rolling Stones and the Beatles and all that stuff, and it was profoundly different from the music I heard on the radio at the time. It was like there was something extra, something important, more interesting to listen to, in certain groups from that time period. I grew up thinking, “Wow, this is different.” I knew it was different. That all music wasn’t the same. I knew which groups I liked. I had very distinct tastes as a kid. I liked Johnny Cash, but I didn’t like all country music. I had some kind of discernment from an early age. It was really weird. I don’t know where it came from. My parents are not very artistic, you know. They’re not anti-art, but they weren’t proponents of it in any way. So it wasn’t in my background, per se.

Benner: But you wanted to be a musician?

Buchanan: I knew that I wanted to find a way to do the things those people were doing. But I’m not a musician. I didn’t have that talent. I tried to play the trumpet, the trombone, the tuba—but I was terrible at it. I knew that playing music wasn’t going to be my ax. But I had this natural talent for drawing. I could draw. At an early age I drew pictures of myself. I drew pictures of my teachers in art class.

And they actually looked like the people they were supposed to be. Which was kind of unusual for a seventh grade kid. And I think those teachers told my parents, “Your kid’s got something going on here.” So my mom took me to the Asheville Art Museum and I took drawing classes. And I learned how to do contour drawing and other things, and I became obsessed with being an artist. I was a strange kid.

As a teenager, I was kind of a big strong guy, and I got corralled by the school and my parents, “You’ve got to play football!” I was good at it, but I hated it. And I didn’t care who won the game, as long as I did well. That’s all I gave a damn about (laughs)—me doing well! I was happy as can be, even if we lost. The coaches hated me, because I wanted to laugh and sing after the games like we had won. I was always getting into trouble. They were like, “We lost! You shouldn’t be celebrating!” and I was like, “I played well. I made lots of tackles,” and they were like, “This is a team sport!” and I was like, (sigh) “OK.” I remember telling the coach, “I did a lot. I was one of the best players in the game,” and he told me to shut the hell up.

Benner: Beautiful.

Buchanan: Bad attitude.

Benner: Did you already know by high school that you were going to study art?

Buchanan: No. It was always presented to me by the adults in my life as a pipe-dream, and if I was ever going to make art for a living, I was going to have to go into advertising. I actually made plans to become a commercial artist (sigh). I went to Charlotte to look at some schools and that kind of crap, and . . . nah, I didn’t want to do that. And my parents didn’t even want to pay for that.

I didn’t really know what I was going to do with my life. So, I went to Mars Hill College and got a degree in history.

Benner: But you didn’t give up entirely.

Buchanan: Well, no. I have a minor in art from Mars Hill College. I took as many art classes as Mars Hill would let me take. But at the time they didn’t have a very strong art department, and I thought I’d be throwing my money away if I went for a degree in art there.

Benner: That’s where you started painting. How did you get from doing realistic drawings as a kid to becoming a painter? How does that progression go?

Buchanan: OK. Well, I was an awesome drawer, and I just got better and better, but I was not a very good painter at first. I was terrible. Drawing was natural, but painting was very awkward.

Benner: Why? Because you had to use a brush instead of a pencil?

Buchanan: You have to learn it, you have to—it’s probably like dance, probably no one’s really good—I mean you can dance around in your own life, but once you get a teacher and they say, “This is the right way to do things,” then it probably isn’t as easy as being a free spirit, and just freestyle or whatever. So it was a lot tougher. It was an adaptation. I think for the first two years my paintings weren’t that great. They were pretty good. But even when I was stinking I never stopped. I made another one, and another one. I wasn’t just making them to make them; I was making them the best I could.

Eventually I got to where I made my first powerful painting. It was a still-life. Somebody stole that painting, so I never got the pleasure of taking a picture of the thing, but it had an almost trompe l’oiel feeling to it. It was a cow skull and like . . . bone fragments, and it had a real depth and dimension that I had never put into my work before. I made that little milestone, and all of a sudden I knew how to do it. I had made my first good painting.

After making about thirty bad paintings.

Benner: But you got a degree in history.

Buchanan: I got a degree in history. I tried student teaching, but I was a really horrible student teacher. I was a good history student, but I had no business trying to teach history to kids. Because I didn’t care about teaching the kids, I just liked history. I didn’t like kids. And I was way too immature at twenty-five to want to be doing that stuff. I still wanted to play . . . and learn, and grow.

Benner: Not to be a grownup all of a sudden.

Buchanan: I knew that if I chose that as my life, I’d be having a heart attack in about five years. I felt so stressed out all the time. I hated it. And it wasn’t so much the kids that were hell, it was the other teachers that were hell. I hated them. I felt like I was being stared at. I was teaching at this horrible redneck high school called North Buncombe. When the principal showed me around, he said, “I designed this school like a prison.” Each hall went out like arms from the center, and you could stand in the middle of the rotunda and see straight down all the halls at the same time. All the lockers had been built into the walls so nobody could hide behind them or anything. He was very proud that he had designed this prison high school (laughs).

I knew I had to get out of that.

So I became a dishwasher and an art student, and I went to UNCA after I graduated from Mars Hill. But UNCA didn’t want to accept any of Mars Hill’s credits, and I didn’t want to take all the math, all the science—everything all over again. So I didn’t take an art major.

At UNCA I didn’t have a girlfriend. I didn’t have any money. I had lots of friends, and lots of party time, but I knew I wanted to get serious about something. And I knew that it was possible. I didn’t believe anymore that it was impossible to make a living being an artist. I knew that if I believed in it hard enough, I could make it happen. I don’t know why I had this faith, but I did. So I put it out there and kept hammering away at it, and I actually got better and better.

But I didn’t know much about the history of art. The development of art. Where things came from. At school, I did this kind of wild, crazy painting. Outside the studio they had these ceramic heads that the pottery department was making, these surrealist, ugly-looking heads on this wall . . . so I did a painting of all these trees, and each tree was a different color, and the sky was red. To me it was a kind of painting that didn’t look like anything else I had ever made. I wasn’t that experienced with the art world. So when I went into class that day they said, “Oh, you’re fauvist now,” and I was like, “What’s that?” and they said, “a wild beast,” and I said, “I kind of like that,” (laughter) and they said, “Yeah. You would.”

They said it was a put-down to the early expressionists—you know—pre-expressionists. Some critic called them wild beasts because they had no control. They were just working from their intuition, which was a smack against the academy, so . . .

Benner: But it resonated with you somehow.

Buchanan: Well, I went out and found out what a fauvist looks like after that . . .

and I think . . .

but . . .

but I . . .

OK.

Because I had a learning disability . . .

I was not a great reader. When I went to college they tested me. I had maybe a tenth-grade reading level, but I had a grad school vocabulary. I mean I was a smart guy, I listened to people talk, listened for the content . . . but I was very bad with language, and awkward with that sort of thing. I guess I got kind of good at writing papers in school, but after the history degree fiasco was over I never wrote anything. Until recently . . . um . . . on Facebook. I’m actually getting a little better at writing now. But I forgot how to write. I forgot how to spell words. I had to look up simple stupid words when I started trying to correspond with people. But I really didn’t have a reason to write anybody. I had no desire to be a published person. But I don’t want to be an ignoramus either, and I want to communicate well. I want to be understood, because . . .

. . . it’s important (laughs).

Then I moved to Athens, Georgia. I was having a life crisis, so I moved down there.

I stayed for a year. I lived with this poet guy in a trailer. I was a landscaper in hundred-degree weather, and every day I came home caked in red dirt, and the poet . . . the poet would just be sitting there. There was a McDonald’s in front of our trailer court, and I’m like, “Dude, they’re hiring. You’re making me pay for everything, even your food,” and he’s like, “I can’t bring myself to work at McDonald’s. I’m a poet,” and I said, “What do you think I am? Do you think I love sweating to death? Having so much sweat in my eyes they’re bloodshot and I can hardly see? You think I like what the fuck I’m doing? You need to hustle.”

Wintertime came, and I turned all the electricity off. And we both froze. And I was very happy. It was so cold in that trailer. I went to Boston and it wasn’t cold like that. We had no heat at all.

Benner: You were sitting around bundled in blankets?

Buchanan: I looked like a guy who weighed three times as much as I did, because I had so many clothes on. The poet didn’t have anything, and he was freezing to death. But I didn’t feel sorry for him because he had seen me suffering and didn’t give a shit. So I’m like, “Now it’s your turn.”

Benner: Did he get a job?

Buchanan: No. He got a girlfriend.

Benner: Ah.

Buchanan: He got to stay warm. Eventually.

Benner: Then you went back to Asheville.

Buchanan: Yeah. In the spring. I studied art for another year and a half at UNCA, and that’s where I met Suzanne (my ex-wife, artist Suzanne Saunders), and after she graduated, we tried to move to New York.

Benner: Your original choice was New York, not New Orleans.

Buchanan: We researched the various art scenes in America, and decided to try New York. We started by going to Boston, because we knew people there, and it was close enough to New York that we could do our research on moving there. But I couldn’t get a job in Boston, and we couldn’t get a house, so we ended up staying at a friend’s house, or a bunch of friends’ house. Me and Suzanne would move from room to room in that house, until finally we said, “This stinks. We’re getting out of here.”

At one point we threw a dart at the American map, and it landed between Atlanta and New Orleans, and we were like, “Screw Atlanta. We don’t want to move there. It’s horrible (laughs).” We hadn’t even been to New Orleans, but we knew it was better than Atlanta. So we said, “We’re moving to New Orleans,” and we bought our plane tickets.

Then, a week before we left Boston, all these people wanted us. The Boston Museum of Fine Arts wanted to hire me as a guard, and a few other opportunities appeared—but we’d already made our plans. We knew we didn’t want to pay $2500 a month for a little cracker box place in New York, and Boston didn’t have a good art scene at all—we could have accepted Boston—but neither one of them welcomed us in.

So I never got to see what New York was like.

Benner: In 1991 you moved to New Orleans. What was it like for you in the early days?

Buchanan: I was a Beignet waiter for the first year and I wore a stupid little paper hat every day.

Benner: Café du Monde?

Buchanan: No, no. Café Beignet, which is an extinct café. At least for the French Quarter it’s an extinct café. It was across the street from Jackson Square. I worked there for maybe a year, and I kept seeing all these people that sold art across the street. I kept seeing all these people that sold not so great art, and they were out there every day, and I knew they made a lot more money than I did as a crappy Café Beignet waiter wearing a stupid little paper hat. So I quit. Right before Mardi Gras. Didn’t have a backup plan. I went to Royal Street and stood out there for a month. Every day I was out there painting, and trying to sell, and there was this great uncertainty.

At that point I had done all these wood carving things. They took an exorbitant amount of time to make, but people didn’t even want to give me twenty or thirty dollars for them.

Benner: Wood carvings?

Buchanan: Yeah, they were things that I had carved and then hand-painted. I did a lot of those in the early days. I thought I might make prints, but I liked the wood plate better than the finished print. So I made many many plates. I would paint inside the grooves. It took forever to make one of those things.

But the carving thing was not significant to my progression. It was something I tried. I ended up painting all the time, and people responded much better to the paintings.

Anyway, after that first month—on the same day my rent was due—this would-be rock star woman named Poe (who had a momentary pop song called Angry Johnny, if you want to look it up . . .)

Benner: I think I’ve heard of her. (Daughter of Polish filmmaker, sister of House of Leaves.)

Buchanan: Yeah. Well, she bought two thousand dollars’ worth of art from me in one day. That was the most money I’d ever made in my life, and I said, “This is the job for me. This is what I want to do. This is what I came here to do. And now I’ve proved that I can do it.”

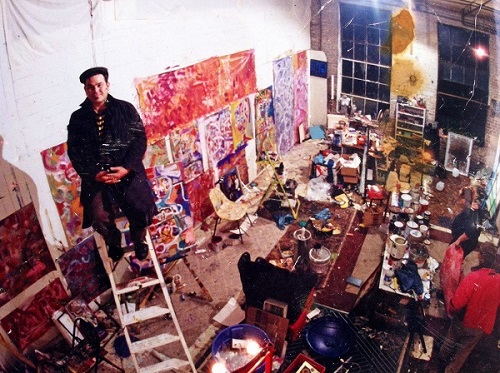

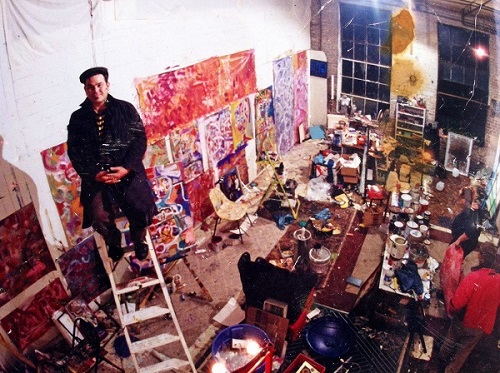

Benner: Did you have a studio then, or did you work out of your apartment?

Buchanan: I did it out of a tiny little apartment on Royal Street. In an attic. It was like going up this endless spiral staircase, and you could see behind the walls of the French Quarter. It was like an M.C. Escher painting, stairways going into walls, and just weird stuff—defunct architecture and still-functioning architecture, a real hodgepodge of time periods—the different owners of the building had built separations and stuff that you could see through . . .

Benner: That’s in the tiny Royal Street apartment?

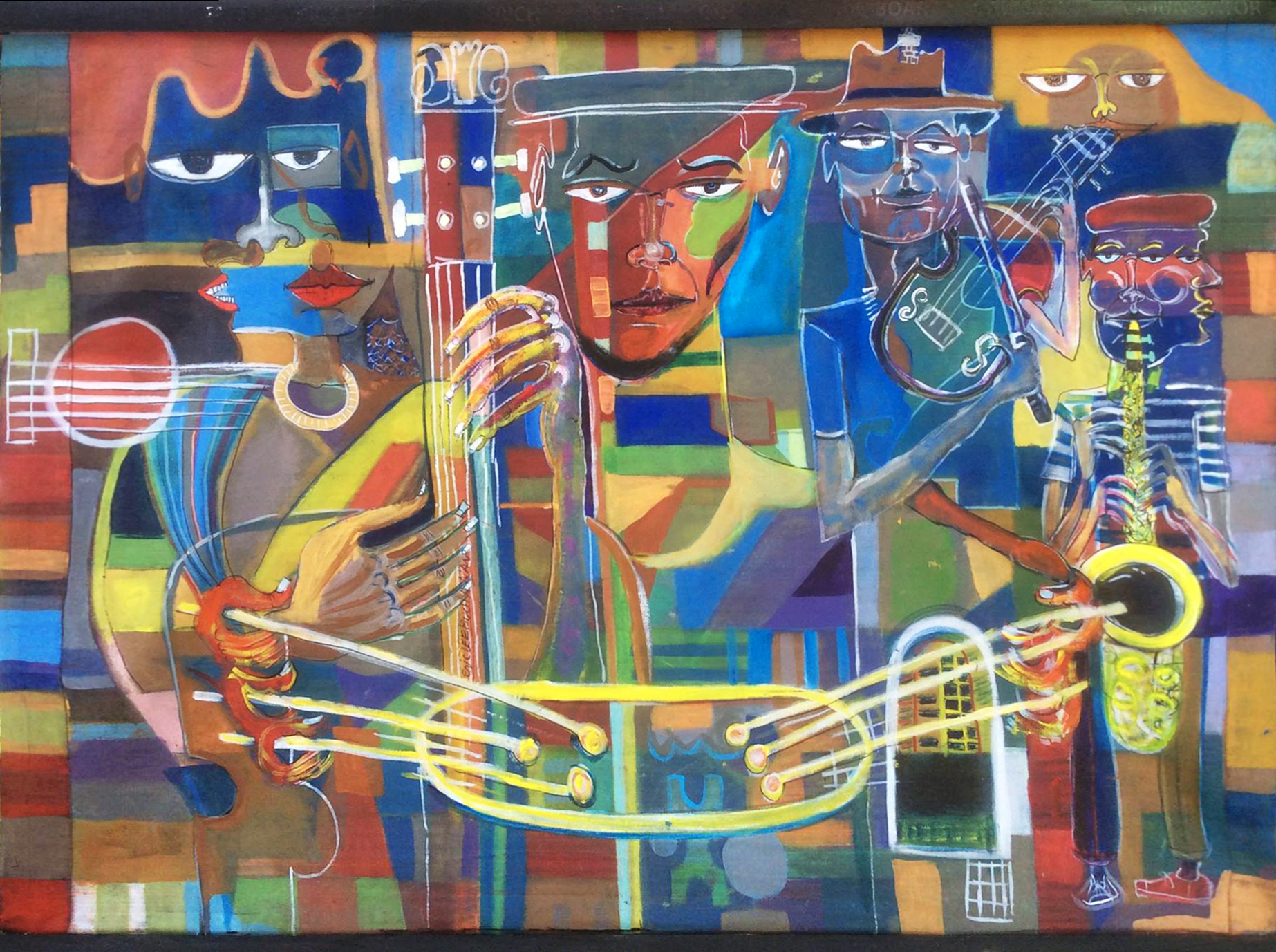

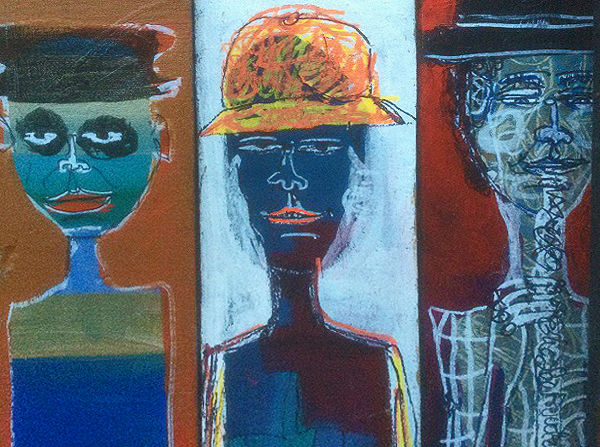

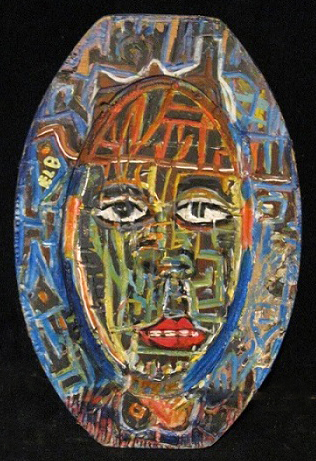

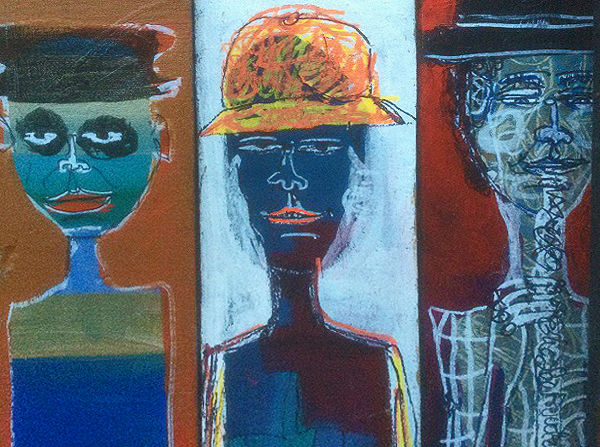

Buchanan: That’s in the building the apartment was in. Anyway, I became endlessly fascinated with every aspect of New Orleans culture, and buildings, and people, and I studied everything, just trying to memorize the buildings and the wrought iron railing patterns, so I could draw and paint that stuff out of my head. I have this obsession with realistic detail, and I also have this kind of crazy abstract expressionist thing. I’m not a true abstract artist. I’m not a pure abstract artist. But I am an abstract artist. Some people want to say, “Abstract art has no picture of anything!” But before there was non-figurative abstract art, figurative artists were considered abstract artists. Cubist artists were considered abstract artists. Then, when non-figurative abstract art came along, they started calling Picasso an expressionist, not an abstract artist anymore. They changed the definition.

Benner: Could you talk a little bit about your technique?

Buchanan: OK. I have this sort of natural thing in my style, to make elongated people, and it may have something to do with my, sort of, oh—how shall we say—dyslexia. It may have something to do with dyslexia and some . . . mild autism. I think a lot of artists have touches of that. And if you’re not tetched too hard by it, it actually makes you a good artist. And I think that explains a lot of my own natural weirdness. That I see and think a little bit differently about space and how to arrange things. It comes out in the art.

Benner: So your style is informed by this distortion in your perception.

Buchanan: Right.

Benner: You sell paintings regularly on Jackson Square, but you’ve done several larger commissions, like the Audubon Hotel façade. Could you talk a little about that?

Buchanan: The Audubon Hotel was this legendary bohemian hotel, which was—Oh God—the best mixture of people. It was the closest New Orleans will ever get to Studio 54. It was wild—sex, drugs, everything. Even people that weren’t on drugs were welcome. It was homeless people, it was transvestites, it was strippers . . . yats from out in suburban New Orleans . . . it was anybody. Anybody that was a misfit went there. They found it some weird way.

I had painted a hotel room in there—several artists were commissioned to paint rooms—I had one, Suzanne had a room too, and people paid more to stay in the crazy rooms. Mine was this kind of weird, expressionistic . . . cubist . . . a happy nightmare I guess you could call it. People didn’t know if it was a happy thing or a nightmare (laughs). It was a little bit of both. Suzanne had this surrealistic room; kind of Bosch-esque is how I would describe it. It was really cool. And there was this other dude named Bubby who had a room, and he had taken a nail gun and nailed thousands of teddy bears and stuffed critters all over the walls. It was 360 degrees of stuffed plushiness. And he even put these insane Velcro bedspreads on the bed. I couldn’t believe it . . . it’s hard to describe (laughs). I mean I didn’t want to stay in that room very long.

So, the owners were happy with our rooms, mine and Suzanne’s, and we were a couple. They liked us both. They didn’t want to offend either one of us, and they thought we could collaborate, so they commissioned us to do the façade.

But we had tried to collaborate several times painting canvases in our studios, and we just ended up bumping egos and not getting along, and not making good art either. But we were very proud to get the commission. So I said, “We’ll flip a coin, and whoever wins the coin toss gets to choose their side, and we’ll meet in the middle, and when both sides are happy with their side, then we get to go over into the other person’s side and put our flourishes on, and unify the whole piece of art.” The ground rule was we had to have the same horizon line, so the picture made sense.

The idea of the painting was you were looking at the outside of the hotel, but you were looking through the building—it was transparent—and you were seeing the people who inhabited the weird hotel bar. So it was a weird mixture of monstrosity and interesting characters.

It ended up being a successful thing and people loved it.

We got a lot of attention.

Then they sold the hotel.

Benner: Oh no.

Buchanan: I met the new owner of it, and his name was Joe the Suit.

Benner: Joe the Soup?

Buchanan: No, Joe the Suit. I was taking pictures of the front of the hotel, and he didn’t know I was one of the artists, and he says, “I like that painting,” and I said, “Yeah? You do? Why don’t you just keep it?” and he says, “Nah. Nah. We’re starting from scratch. We’re gonna gut this whole thing.” Then he says, “You want to stay and watch me sandblast it? Ha ha ha!” I was like, “No, I don’t. It’s your property. You do whatever you want. But I’m not going to stick around for that. That’s going to be a sad moment for me.”

Benner: By this time he knew who you were.

Buchanan: He knew. I told him who I was, I said, “I’m one of the artists,” so he was like, “You want to watch me sandblast it?” He thought that was hilarious. HAHAHAHAHAHAHA!

I can imagine why they call him Joe the Suit . . . a little dodgy (laughs).

Benner: What’s the Audubon like now?

Buchanan: Oh God, it’s a shell. It’s been sitting empty since 1999.

Benner: It’s not a hotel?

Buchanan: Not anymore. It’s nothing. It’s probably in litigation, you know, a lot of times the former owner has liens on the property . . . it’s an open-faced thing. They’ve started and stopped and started and stopped. And they’ve done that with a whole lot of other bohemian paradises. They’re like, “Oh, people want to hang out there, let’s buy it out,” and then nobody wants to hang out there anymore because it’s not cool like it used to be. Their version of cool is not how cool naturally assimilates.

Benner: Could you talk about some of the other commissions?

Buchanan: I painted a mural in Chicago for this nightclub called Bourbon Street. It took me three and a half months to paint it, during the winter. I was in there all by myself, in this cold building that didn’t have bathrooms or anything, painting this mural. During the day there would be about a hundred and fifty people cutting wood all day, so I had to paint at night. I painted this massive ninety-foot-wide, maybe thirty-foot-high mural. It was the stage. I painted all that by myself. I was there for three months. When I first went in there I was freezing to death. I was so cold. They flew me up there, and I didn’t have very many winter clothes, because I live in New Orleans. I didn’t even have a big winter coat. In New Orleans it gets cold for three days, but that’s about it.

Benner: And you painted one in Colorado.

Buchanan: I painted one in Boulder, at a place called Red Fish. Red Fish is a microbrewery, and a restaurant, and a billiard room . . . they had these monster steel brewing vats . . . multi-million dollar deals to construct that shit . . . and the Chicago thing was a multi-million dollar thing . . . although I didn’t get paid well, in either case . . . but it was all very educational for me, because I never worked with a contract.

Now, if I do something, I want to know exactly what I’m going to get paid, and I want them legally responsible to pay me after I do my work. Not what they think I deserve, but what I charge them. People will exploit artists, and if you’re an artist and you get a commission, get a contract.

And if you have an exhibition in a cigar shop or a restaurant, make sure those people are not going to steal your artwork. Because that happened to me. The La Habana Cuban cigar shop tried to steal my art, and I had to threaten to sue them.

Benner: What happened?

Buchanan: They said they wanted some art for their shop, to decorate the place. So I gave them two pieces. But I put really exorbitant prices on them so no one would want to buy them. I didn’t want to sell them, and they knew that.

Benner: The paintings disappeared?

Buchanan: I went to the place and I said, “Where are my two paintings?” and they said, “Well, we want to buy them,” and I said, “I put those crazy prices on them because I didn’t want to sell them. They’re important to me. This is what we agreed to from the beginning. Now you’re changing everything?”

They had taken the paintings off the premises. They weren’t even in the building anymore. And I was like, “Well, I’m going to cost you every time we go to court, because my lawyer loves to kick thieving greedy people’s asses. He works for the ACLU. He will kick your ass. And I don’t even need a lawyer, all I have to do is go to the police and file a charge. So you can never ever sell that art ever again, because it will be hot. So, you do whatever you want, but we’re going to resolve this today, or we’re going to start going to court soon.” (Sigh) It was the most crazy . . . anyway, they gave me the money. They paid me for the art.

So now I know that you’ve got to have a contract, and be professional, or people will exploit you. Now that I’m getting better as an artist, and my prices are going up a little bit, you know, people will steal from you. People may sound goodhearted and like they’re your real fan, but it doesn’t mean they won’t steal from you. They may be your real fan, but they’ll still steal anything they can. They will get over any way they can.

It’s called business.

Benner: You’ve had to develop your own practices through trial and error.

Buchanan: There are some things I won’t do. I won’t paint a portrait of anybody’s child. I only paint portraits of people I know, or like. There has to be some sort of relationship if I paint your portrait. Or I particularly like you.

Benner: So most of the people in your paintings come out of your imagination?

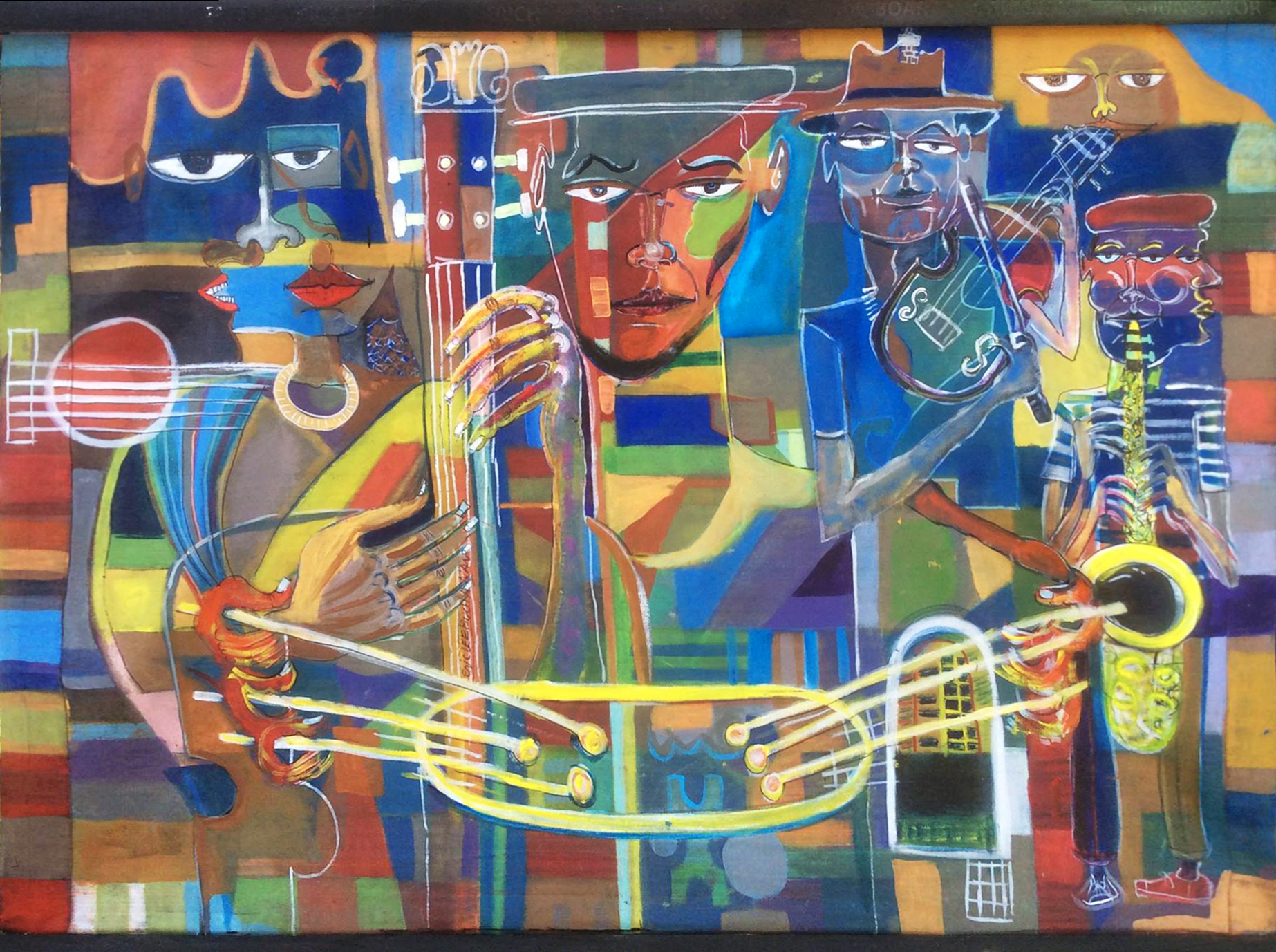

Buchanan: Yeah. Or they’re people I know. Actually, I’ve been out there on Jackson Square for so long I know so many street musicians, and I go to bars where jazz bands are, and I know who I like. And they become familiar recycled characters in lots of paintings.

Benner: Washboard Brad?

Buchanan: Washboard Brad. Guitar Paul. Tuba Fats. There’s all these people in New Orleans, and they don’t need to know my last name, either. I’m just Eric the Artist. And they’re Tuba Fats. Everybody’s got their handle. These are my peers, you know. Work peers.

Benner: You see them regularly.

Buchanan: Every weekend. Every festival. And I see them walking around town, at the coffee shop, or the bar. Wherever I be, they’re there too. Some of them, I run into them at the snowball stand . . . whatever (laughs).

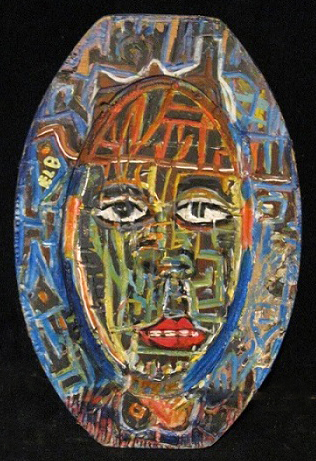

Benner: What’s your method? How do you approach making a painting?

Buchanan: There are several different ways, and there are different types of paintings I make. I have many styles, actually. That can be a strength or a weakness, depending on how you perceive it. Because I can make one painting that’s pretty darn realistic, like a cat out in a field, and it’s straightforward. I try to capture the mystery of this cat out in the field, with the moonlight in the background, and the high grass as tall as he is. And all the detail makes it come to life. It’s always a story, and I punch it up where it needs to be, and more reserved in other areas.

There are those kinds of paintings, and then there’s the more abstract subject matters that I do which are sort of a fusion of abstract expressionism, surrealism, and cubism. Primarily cubism. I take these elements of expressionism and surrealism and I cubify them, so I can tell a story using elements of my thoughts and experiences in life. I kind of feel like I’m a filmmaker, except I only have one frame to tell the story in.

I like doing both kinds of work, and I see the value in them both, and there’s no conflict of interest in me to paint something realistic, or half realistic, or totally like a cartoon. I don’t put limits on myself, and I feel like I can—and I will—paint anything I want to, anything I can think of, and try any experiment I want. I don’t feel like I’m owned by pressure from a gallery to make this certain type of thing that sells, and stick with that because anything else will confuse people. I don’t care. I like being an independent because I don’t care if it confuses my audience. This is what I like.

And I want people to see each piece as an entity unto itself. Occasionally I’ll do a show that has a thematic thing, and all the paintings relate to each other in the style, but then there are other shows where there will be seven realistic paintings and ten crazy chaotic abstract paintings that are borrowing styles from a whole bunch of things. I think this gumbo of fashion came out of being in New Orleans for twenty years, and hearing every kind of music that you can imagine, and seeing every kind of human being that you can imagine. If you stand out there on Jackson Square, you’ll see the highest and the lowest of everything walk by you at some point. So I’m inspired by my people-watching, I’m inspired by the buildings, I’m inspired by the sky and the giant clouds they have down there, and all the water.

But there’s more to life than just New Orleans, too. I don’t want to be pigeonholed as just a New Orleans artist. I’m a bigger artist than that. I don’t want to be called a Southern artist, or a folk artist. I don’t mind being called an expressionist, or an abstract artist—those are more like what I am. But I’m not a folk artist. I know too much about art. I’m too self-aware. That’s for people who are truly naïve. I get kind of irritated by the label folk, because I’m not a folk artist. Not in any sense.

Benner: Implies a primitive sort of thing . . .

Buchanan: It’s like an old farmer in rural Alabama who sees Johnny Cash on TV and paints a very crude picture of Johnny Cash. Now, that’s beautiful art. I’m not taking away from it. But that’s not me. If I painted Johnny Cash crudely it’s because I chose to paint him crudely. If I wanted to paint Johnny more realistically and dimensionally, I could do that too. It depends on what suits my fancy.

Benner: So long as it’s a painting of Johnny Cash.

Buchanan: It could be Bob Marley (laughs).

Benner: How do you balance the need to make money—I mean, I remember you once said, “Cats sell. If you need to make some money quick, paint a cat. Somebody will buy it.” I know you do what you want. But you also have to sell. How do you balance between being a commercial artist and being an uncompromised visionary?

Buchanan: I’m a terrible businessman and I don’t have a plan for success. I actually stopped making the things that sold the best—the stick figures on the long planks.

People were begging for them, but I stopped making them, because I didn’t want to make them anymore. I started making my big paintings, and I stood out there until I sold them. There were so many weekends in a row that I didn’t sell anything.

But eventually the dam bursts, and I sell three or four paintings in one day, and it changes. My survival strategy is that when I have that day—and it may take a whole month of standing out there to get to that day—I’ll pay my rent ahead, months at a time. I’ll figure out how I’ll eat (laughs), but I’m not going to be put out of my home. I’m well paid ahead. I guess that comes from the gnawing insecurity of not having the guarantee that at the end of your time, you’re going to get a payment. It’s a little uncertain, but I think it’s made me a happier person. I have no expectations. I don’t get disappointed if I don’t get what I want. I know if I keep sticking around and trying, I will get what I want, because it’s good, and I know it’s good, and I believe in it, and it will work.

And it does. Eventually the right person shows up.

One time I painted this crazy abstract painting and the character was made up of geometric shapes and sort of . . . slashes or whatever, and I saw this man’s face in it, and I brought it out, and separated things from one another, and I made this really nice painting. It was this man with a bowler hat, and he had a big cigar . . . and he was real to me somehow. I felt great about that picture. Then when I was out there selling, I was like, “This is a hot painting, but nobody wants to buy it.” Everybody was going, “that one, that one, that, one,” pointing to other pieces. I didn’t understand it. And I was charging a very fair price for the work.

Then this man showed up, and it was him. It was his face. It was exactly him. He says, “Do I look familiar?” and I said, “Yeah, you’re the dude in my painting,” and I wasn’t even looking at my painting at the time. And he goes, “Yeah, that’s right. I want to buy that from you.”

I took a picture of him, with his cigar—he actually had a cigar in his mouth—pointing at the painting. He had a fedora on; he didn’t have a bowler on. That was the only difference. I painted the character with a bowler, not a fedora.

But this dude shows up and he’s a dead ringer for the guy I painted.

So it sort of let me know that . . . the universe has a proper place for my paintings to go. I mean, I have this bizarre faith—or superstition—that each painting I care about is supposed to go to a specific place. I don’t have a clue who it’s supposed to go to. But it’s my destiny to make these things, and to have them go to the right people out in the world.

~

Born in Asheville, NC, in 1964, Eric Lee Buchanan has lived and worked in New Orleans since 1991. The text is from an interview with Lawrence Benner conducted on September 12th, 2016.

The images and photographs in this interview are the property of Eric Lee Buchanan except where otherwise noted. Additional photographs and photo editing by Jennifer Coates.