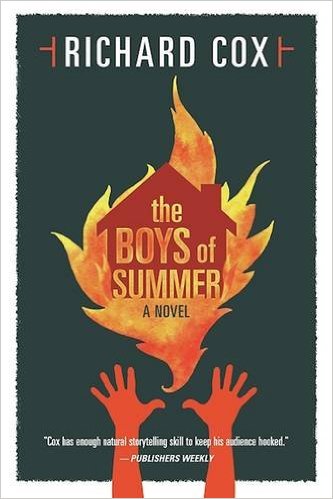

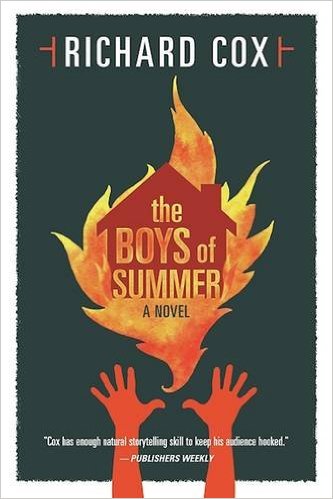

Richard Cox spins a cyclonic yarn of a tale in The Boys of Summer, which releases September 6, 2016, from Night Shade. As equally driven by plot as it is character, Richard Cox’s latest allegorical science fiction novel registers an EF-5 in excitement and non-stop action that will suck you in from page one and leave you shaken and never looking at the world the same by storm’s calm, earning itself a spot on a shelf-end display alongside masters of the genre Stephen King and Philip K. Dick.

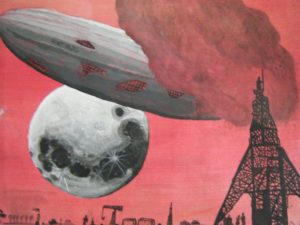

A supernatural thriller set against the historical backdrop of Terrible Tuesday, the April 10, 1979 Red River Valley tornado outbreak in Wichita Falls, Texas, The Boys of Summer tells the coming-of-age story of a band of boys, “survivors” if you will, four years later in 1983 as 13-year-old Todd Willis awakens from a trancelike comatose state endowed with remarkable abilities that, at first, seem only weird and more mature for his age to his newfound adolescent friends in his neighborhood.

As the summer months begin to wane, a series of terrible events befall the town of Wichita Falls that will tie the boys together for all eternity, a mystery awaiting in the ashes to catch fire once again. Flash forward 25 years later and a new threat is on the horizon in the small Texas town, a legend foretold in Native American folklore—something far more dire than the vortices of 1979, something apocalyptic and vengeful. When the borders between reality and fiction begin to merge, the boys-now-turned-men realize that Todd’s once exceptional gifts of youth were not merely unusual or resigned to their own misperception, but otherworldly, and the answer that may thwart the deadly consequences they now face.

If a future is to be held for any of them, the men must confront their childhood past. But are those days gone forever? Is it too late for Todd, Jonathan, Bobby, David, and Adam? Has the story’s ending already been written and what new evils and sheer madness will be unleashed by trying to stop it? And what really happened to Joe?

Seek shelter at your local bookstore to find the answer.

THE BOYS OF SUMMERBy Richard Cox436 pages. $11.99. Night Shade (September 6, 2016)Amazon | Barnes and Noble

I caught up with Richard last week. The transcript of our conversation is below.

So, before we even start, let me just say, I really enjoyed this novel. Thank you for taking the time today for this interview. I want to get that out front and center for the reader immediately and it not be buried deep within the interview and covered with a concrete slab you’d need a jackhammer to get to.

Well, that’s nice of you to say. I’m glad you enjoyed it. I appreciate that. As a writer the first thing you always want to say to that is why—why did you enjoy it?

The Boys of Summer is one of those novels that once you start, it’s super glued to your hands until the last page. There’s no putting it down. I missed seven meals and lost five pounds, and needed a literal shot in the ass at the urgent care center once Tawakoni Jim’s revelation sprang forth on the page like a ball of twisting fire. Actually, that was from a mysterious insect or spider bite I received the same day your book arrived in the mail. Even so, this is a rewarding read. A “who cares if I’m dragging ass at work tomorrow, I’m staying up to finish this” kind of novel.

That’s very flattering and obviously the effect you hope to have on a reader. That’s hopefully what the opening tornado scenes do.

The opening pulls you in from the jump. The first sentence for that matter: “If you believe legend, the city of Wichita Falls was doomed from its first day.” It was game on for me, as a reader, right there.

I had always heard when I lived there that “the Indians told white men not to build a town where Wichita Falls is because of all the tornadoes.” But when I Googled that, I didn’t find anything of the kind. I think people were creating their own legend, as people are wont to do.

Give me your elevator pitch. What is The Boys of Summer about?

The Boys of Summer is about a group of boys who descend into a summer of darkness in 1983, and who are forced to reexamine that darkness twenty-five years later when it returns to haunt their hometown again.

Why this story? Any particular motivation?

I think every novelist has a coming-of-age story in him, and this is mine. Even though the plot has nothing to do with anything that actually happened to me, I borrowed certain events and concepts from my childhood to bring this novel to life. However, the novel operates on many levels. One of them is related to the time frame of the story. It’s no accident the town is destroyed in 2008, for instance.

Let’s talk about that. You grew up in Texas, but now live in Oklahoma. Were you familiar with the events of 1979 in Wichita Falls, Texas? Was there any connection? The historical backdrop of Terrible Tuesday plays such a critical role at the onset of the novel.

My family is from the area, and lived in Wichita Falls during high school, but we didn’t live there when the tornado hit. However, we visited just a couple of days after Terrible Tuesday. The town was still off limits to non-residents, and in order for us to see the damage, my uncle had to drive to the city limits and pick us up. What I saw as we drove through a town that had nearly been wiped off the map—20,000 of the 100,000 residents were homeless after the storm—has stuck with me ever since.

That must have been pretty devastating to witness, even the aftermath.

It was the most damaging tornado in American history at the time, and wasn’t surpassed for more than twenty years.

How old were you?

I was eight. It’s part of the reason I became fascinated by the weather and eventually became a storm chaser. I was curious to write about how such an event would affect the town and the people who lived there.

So, you’re eight, you see this, the aftermath of Terrible Tuesday in Wichita Falls. Entire lives changed. A town nearly obliterated from the map. The characters in your novel are impacted when they are roughly eight or nine years old.

Correct. I wrote the characters similar in age to me because I wanted to write about cultural experiences of my own childhood.

And seeing that at your age obviously a bit of impetus to becoming a storm chaser later in life it sounds.

Exactly.

Tell me about storm chasing. What is the reality? I’ve seen Twister, but I don’t trust any film with Bill Paxton playing lead. Heard Goo Goo Dolls singing “Long Way Down” in the background. What’s it really like? Flying cows. Does that really happen?

Anything in a tornado that is transported through the air is done so in a rough and violent manner. Cows can certainly fly, but any winds strong enough to whisk a cow into the air are going to be in excess of 200 mph. That means the cow, instead of floating, would by flying by so fast that it would liquefy anything it hit.

So, let’s discuss the obvious. The title harkens back to Don Henley’s 1984 hit by the same name, “The Boys of Summer.” I’ll be frank, not my Christian name, and say, I was a little skeptical as to how you were going to pull off the Don Henley song as a vehicle driving the story forward. I kept thinking, This is risky. How is he going to do this? But you pulled it off. Boy, did you pull it off. You reeled me in and I became just another fish on a hook waiting for my ride to the frying pan. Grease sizzling and popping below me. Tell me, why this plot device?

The funny thing is in the original drafts the song wasn’t included. It wasn’t part of the story. I just liked the title. But I was enamored with the idea of someone knowing about music that they shouldn’t have, how they would look like a genius having written it when they really hadn’t. And I lucked out that my time frame was 1983 and the song was released in 1984. Total luck.

In a way, it becomes the soundtrack of the story, but in a mysterious manner that is slowly revealed to the characters. Jonathan hears it, David, Bobby, Adam. Yet no one puts two and two together.

Yes, the characters never put it together, which seems curious as you’re reading it but which hopefully becomes clear later. I borrowed the idea from an episode of Otherworld, a television show in the 1980s. The characters inhabit an alternate reality, and in an episode called “Rock and Roll Suicide,” they form a band and play rock music hits from their world and become famous doing it. So I imagined Todd had been touched somehow by an alternate reality, what seems like the future when you first read the story, but which is revealed to be something else later.

This book is all about the reveal. And the adolescent magician at work in The Boys of Summer is none other than Todd Willis. Who is he?

Originally Todd was going to be the villain, because he would draw the other boys into a summer of darkness in 1983. And he still does. But now he’s more of a tragic figure, someone who was affected by the tornado in a way that changed him, and that he shares with his friends because he really has no choice

So, there’s Todd, who woke from a four-year coma. He’s the kid with the exceptional abilities; or, actually, he’s the only kid who realizes he has exceptional abilities.

Yes. Others do, but his is the most obvious and he’s the one who realizes it.

Then we have Jonathan and Bobby, David, Adam, and Alicia. And let’s not forget about Joe. Joe haunts the novel in so many ways.

Yes, I love how Joe “enters this story doomed from the first word.”

There are a lot of characters in this book that each play fairly significant roles in their own way. That’s tough to do, and really, I can only think of a few narratives that manage this well: It being one of them, which Booklist drew comparison to in its review, and Stand By Me, the film adaptation of The Body, also by Stephen King.

I was worried about balancing so many characters and rendering them believably and differently enough.

How you laid this novel out is no small feat. It starts out in 1979 and follows each character as they face the great tornadoes of Terrible Tuesday. That’s tricky and proves fatal to many narratives. Most novels can only balance two or three characters. You start with five and then add a few more along the way. Then you immediately switch to 2008, 29 years later. Then we’re in 1983.

Thank you for that. I hope others feel that way, because it could obviously become confusing. Many point-of-view characters and non-linear storytelling among several timelines.

Are you aware of the Booklist review from David Pitts? To quote Pitts: “This beautifully written supernatural thriller will no doubt remind some readers of Stephen King’s It, and perhaps also of Dennis Lehane’s Mystic River, but make no mistake: this is no knockoff. Cox’s story is vibrantly original and his characters are intricately detailed.”

Yes, I’m aware of that review and I’m honored he wrote that. It seems he took from the novel exactly what I hoped to achieve.

It goes back to the bond and simultaneously the turmoil boys have with one another at that age.

For sure. In the 1983 section, after the fight between Todd and Bobby, everything progresses very well for the boys, and then suddenly everything goes to shit. And is why eventually they make some very poor decisions.

Which is very much how boys can be at that age too. Roll around on the ground and punch one another in the nose, then go find a can of gasoline. Contrary to what my own children may ever come to believe, I, too, was once a 13-year-old boy, and the scenes and the dialogue that take place in The Boys of Summer, the nudie magazines, the hideout in the woods, the pack of Winston cigarettes and warm beer stolen from your dad’s stash, the fascination with fire and the lack of understanding of consequence, the admission of masturbation amongst friends and the one kid lying through his teeth he doesn’t do it, this book nails it. This book takes on the universe AND the universal theme of being an eighth grade adolescent boy, and nails it. Occasionally I’ll tell my wife stories from my youth, and she’ll just stop me dead in my tracks and say, “Yeah, please don’t tell me anymore.”

Thank you.

Your book is wholly original, but there are the obvious nods to Stephen King, and even his alter ego Richard Bachmann. Was Stephen King an influence for you in any way? Note: I never put my ankles down near the bottom of the bed because I thought a small child named Gage was going to cut my tendons with a razor knife like was done to Jud Crandall in Pet Sematary.

Yes, I acknowledge Stephen King in several ways. Both directly on the page, and in references to his stories. Todd’s coma is reminiscent of The Dead Zone, and that novel is also mentioned by name. Then Jonathan believes he has come up with an original idea about a writer, Paul, who is held captive by a woman, Annie, who is his number-one fan.

Starring James Caan.

He has no idea at the time that he’s thinking of the novel Misery. This other reality is affecting him and he doesn’t realize it.

And Kathy Bates who seriously looks just like one of my seventh grade teachers. Same name too. Well, first name.

Don’t so many teachers look like that?

There’s one in every middle school.

Stephen King was a huge influence, but of course so is Philip K Dick. The underlying reality of the story owes much to him. And also is connected in ways to my third novel, Thomas World. And I’ve learned a lot from reading Jonathan Franzen. The Corrections wonderfully juxtaposes childhood with adulthood.

Okay, so here we go. Philip K Dick. A man who has been described as “The Man Who Remembered the Future.”

That’s a wonderful description of PKD.

I caught the connection with Thomas World too. Call it a shot in the dark, but I feel you’re aware of what Elon Musk, founder of SpaceX and Tesla, recently said, “There’s a billion to one chance we’re living in base reality,” meaning we’re just characters living in someone else’s simulation.

Oh, yes, I’m aware. I don’t know about those odds but I think it’s more likely we’re in a simulation than reality. I think there’s a 50-50 chance we’re living in an alternate reality of some kind. I’m fascinated with the idea and keep coming back to it in my fiction.

I was about to say, this novel, The Boys of Summer, and your past novels delve into this and similar themes.

Because what is fiction but an alternate reality? It’s difficult to write a novel and expect people to read it without acknowledging we are participating together in a shared alternate reality. But as I say in the book, in the end it doesn’t matter. You’re forced to accept the reality you’re presented. What else are you going to do?

Fiction is such a shared experience. Almost out of body.

Yes, and it’s hard for me not to acknowledge that directly to the reader. It seems disingenuous otherwise.

When I was reading The Boys of Summer, even though the storylines themselves are entirely different, I was reminded of a short story I wrote what feels like long ago in my early 20s.

What was the story about?

It was based on what I suppose you would call a campfire story my grandfather used to tell me when I was a kid and spent the night at his house. In a way, it was horror but it was also science fiction. Alternate reality. In a nutshell, a man is abducting children in the neighborhood and the authorities are unable to generate a lead on the case. Then, and I’m giving the story away here, a young boy from the neighborhood, only one of two children remaining, sees an elderly man leading a child to his basement which is below ground entirely. So the boy inspects the scene and enters the room with the other children when he thinks the old man is away. Except, what the boy doesn’t realize is that the elderly man knows very well the boy is snooping around. He’s written the narrative that leads the boy into the basement. The twist is that, this story is supposed to be a story, not an actual event. And the boy hearing the story realizes it is him in the story at the very end, except, it’s too late. He’s in the old man’s house. The old man is his grandfather. It’s been a while since I thought of it and I’m doing a hack job explaining it.

I love that. And very similar to The Boys of Summer. The act of reading the story creates reality for the characters.

I’m not entirely convinced we aren’t living in some puppeteer’s high tech Atari game from a parallel universe, what with a certain candidate, let’s call him Candidate X, this close to the White House and all. Not to get on the topic of politics, but you’re a novelist, which makes you part of a certain secretive club of sorts; is Candidate X really just a character in a Carl Hiaasen novel and this is all some weird satirical portrayal of the perversity of American politics?

I wouldn’t be the first to suspect a certain candidate is entertaining us all with the greatest piece of performance art in the history of American politics.

It’s like I said to Sean not long ago, one day Candidate X (okay, the great unveil: I’m talking about Trump) is going to tweet to his followers and say, “You suckers. I’m just messing with you dumb a––holes. This joke’s gone too far. I can’t take it any longer. I’m secretly hijacking the election to drive the final nail in the coffin of the Republican Party.”

I have been hoping all this time that he’s doing exactly that. And will someday do that. And where will that leave those disenfranchised voters who refuse to acknowledge their own candidates are the ones hurting them?

That too. And they exist. It’s just so misguided with this candidate. There are real gripes people have and should have. I’m from a place that got smashed by free trade in the 90s. Devastating. Entire towns like ghost towns now. But righting the ship isn’t with the narrative in place on the Trump campaign trail at the moment. His appeal is not because of a logical plan, but a divisive, dangerous rhetoric.

That’s a good point. Both sides have had a hand in carving out the livelihood of middle America. I mean David dies at the end because the government doesn’t properly bail him out. There are no easy answers.

Let’s go there. Let’s scratch more than just the surface, shall we? Is this novel more than meets the eye? Is there an allegory eluding some readers?

There is definitely more than meets the eye. That the characters represent a wide array of social classes is no accident. That they live in a town where opportunity is nearly non-existent is also no accident. The only financially successful character has fled his middle American town.

David

David.

Wichita Falls could be considered the American middle class. It’s an average town in the middle of nowhere that everyone has forgotten. There was a storm of sorts that happened in the United States between 1980 and 2008. An economic storm.

I remember vividly the one from 2008. I spent six months looking for a job. I finally got a job writing proposals. Found out at my interview I accidentally applied for the job twice. They told me I was “persistent.” I said, “Yes, that’s it. Persistence.” The reality was I had put my resume in for over eighty jobs, and people just weren’t hiring. Firing, was the word. Hiring, not the word. Okay, so now I’m going to have to re-read this and see what I missed knowing this bit of info.

There’s a line in the novel where Todd is imagining a tornado destroying “discriminately” always hitting trailer parks and other low income neighborhoods. But that stuff is pretty subtle.

I do remember that line specifically.

Even my editor said, “Don’t you mean indiscriminately”? And I said, No. It’s on purpose. From a political perspective, certain groups going after the middle and lower classes. Again, very subtle. But purposeful.

You sly SOB.

One of the things I like most about the novel is the many ways you can read it, how nearly everything matters and not always in obvious ways. The adult characters inhabit different classes: the creative class, the lower-middle class, the middle class, the one-percenters. Notice none of the adult characters work in industry. All service jobs, nothing tangible. Well except Adam. He builds houses. But he’s going broke.

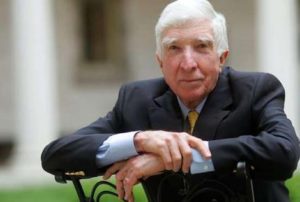

Photo by Kimberly Cox

Building houses as the housing bubble bursts and the Great Recession of 2008 hits. I feel foolish now. Speaking of Adam. Seriously conflicted character. That guy gave me the heebie jeebies. The religious element mixed with this sexual torment caused by his parents. Ticking time bomb waiting to explode.

Exactly.

And we’re flash forwarding from 1979 to 2008. Not exactly boom times for the American economy. Son of a gun, I’m reading this again.

Yes, the present day scenes of the novel take place in 2008 for a reason that is important to readers who want to dig deeper.

History repeating itself. A storm even more dire than the first. Apparently being far removed from college has transformed me from a metaphorical reader back to a literal reader.

There are other alternate realities present. I mean, when David sees manila folders and gets chased down metallic hallways by fuzzy balls of lightning.

Apparently I’ll be reading this three times. Alright, well that about it does it for us. We’ve talked tornadoes, fiction, alternate realities, and fiscal irresponsibility. I appreciate you setting aside some time to talk. It’s been a pleasure and best of luck with The Boys of Summer.

Thank you so much for taking the time to interview me, and for enjoying the book.

One last thing. What’s the most destructive tornado possible? Technical classification.

EF-5 is technically the biggest. There’s a theoretical EF-6 but it’s not an official classification. Probably 315 mph is the wind speed limit.

In that case, The Boys of Summer registers an EF-5 for excitement and non-stop action, and apparently, also for allegorical qualities as it relates to historical economic downturns. If we’re talking theoretical, I’m giving this an EF-6. It was a page-turner all the way.

Well thank you.

You’re welcome. Enjoy the rest of your Labor Day weekend, and, uh, stick with tornadoes. I hear you guys had an earthquake Saturday in Oklahoma. Don’t be greedy with Mother Nature. Leave something for the rest of us.

Is this real or not?

Two veterinary technicians are holding a stretcher at the door when we arrive, but I carry her to the back room myself, lowering Cabo onto a stainless steel table as three vets busily encircle her.

Two veterinary technicians are holding a stretcher at the door when we arrive, but I carry her to the back room myself, lowering Cabo onto a stainless steel table as three vets busily encircle her.

In a hushed, sun-drenched room on the top floor of the hospital lay my dad, tubes coming out of his mouth and his nose and a bandage on his head, surrounded by a bank of machines softly beeping. A broad-shouldered African priest with sad eyes stands by the bed and when he sees me, he envelopes me in a massive hug. “Courage,” he says.

In a hushed, sun-drenched room on the top floor of the hospital lay my dad, tubes coming out of his mouth and his nose and a bandage on his head, surrounded by a bank of machines softly beeping. A broad-shouldered African priest with sad eyes stands by the bed and when he sees me, he envelopes me in a massive hug. “Courage,” he says.