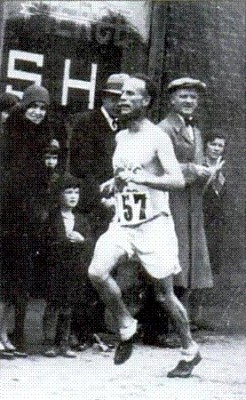

RAISED IN AN orphanage, Clarence de Mar was not the sort you’d think could become a runner. At the time, the sport was more Chariots of Fire than his childhood suggested, and he would have been more likely to be a boxer or brawler. But, he entered the Boston Marathon in 1910 at age 22 and finished second. That year a doctor told him to stop running. De Mar had a heart murmur; he might die. He ran the next year and the course doctor tried to convince him not to start and told him if he felt weak or tired to stop. He came in first. He set a record. He then went to the Olympics and did poorly, got an associates degree from Harvard and worked as a printer, and went to war. After barely training for the intervening decade, he raced in Boston again in 1922. And won. And kept winning nearly every Boston Marathon for the following decade except for 1925 and 26 when he came in second and third….

Clarence de Marathon he was called. He wrote a book later about racing, a memoir, this before runners wrote memoirs. Called simply Marathon, it was published in the Thirties. In it, he said: “Do most of us want life on the same calm level as a geometrical problem? Certainly we want our pleasures more varied, with both mountains and valleys of emotional joy, and marathoning furnishes just that.”

He also wrote in it: “I sometimes feel that the whole word is divided into those who pay attention and accomplish things and those who distract attention and are infernal nuisances. The runners are paying attention ….”

I don’t know if the world is divided between runners and non-runners (I am a non runner but burnish a mighty respect for marathoners) but I know today April 16, 2013 the world feels divided. And, the thing that’s clear now at 6.47 a.m. as I type this is that the line fracturing it is as yet unclear.

~

Twenty-six point two miles is a test. The marathon is a race of attrition and exhaustion. It’s you against yourself and odds and weather, trying to tackle roads and hills. Not bombs.

In a sense the race is existential pushing the boundaries of what is humanly possible. It’s meant to commemorate the run where Pheidippides sprinted from Marathon to Athens to announce victory in the war with the Persians. “Rejoice!” he called, “We conquer.” He collapsed afterward and died. The history of marathon might be tied to war, but that is not its legacy, not death, not bombs, not war.

~

I remember reading a quote from, I believe, Joan Benoit Samuelson, who won Boston in 1979 and 1983 and the first Olympic women’s marathon, about how if there was something wrong as you ran, it ate at you in the race. You’d focus on that one element, something in your insole, a lace that was flopping on your shoe, a seam, a hem…. Your focus would be reduced to this one element as in a kind of Zen of pain, and what you might be able to take for miles three to ten (Samuelson was a woman who ran an easy ten miles in the snow in New England the day she gave birth to her second child, so for her ten is easy.), but at mile fifteen, the distraction is all consuming, your attention reduced to this one element. It’s almost Beckettian in its nature.

Samuelson was on the course yesterday in Boston racing again to celebrate the 30th anniversary of her last win there – when she set a record and beat her nearest competitor by seven minutes. Her goal yesterday was to run within thirty minutes of her record set 30 years ago. (A play on the 30s). She’s 55 and last ran competitively in 2008 for the Olympic trials. There are countless reasons she is my hero, but those are some of them, not to mention running the day she gave birth.

Marathon is the sport where heroes are made, and Boston is the place it happens. It’s the oldest annual marathon in the world, established in 1897 the year after the first Olympic marathon held in Greece. The US competitors wanted to bring the race here. Boston is where duel in the sun, the legendary race between Alberto Salazaar and Dick Beardsley, took place, while Boston Billy, aka Bill Rodgers, won four times in the Seventies and inspired Americans to take up running as jogging boomed across the country. In 1966 Roberta Gibb Bingay, home to visit her family in Boston, hid in the bushes so she could compete. The next year a runner named K Switzer took to the course – the “k” standing for Katherine. She qualified and was officially entered, but no one knew she was a woman, at least none of the officials. She wore a loose sweat suit and kept going until an official dragged her off. The photos were shocking. It was a rallying cry for women and sports. Until then people – men, doctors—believed to run any distance our uteruses would fall out, sterility would ensue or worse. But, in 1972 women were allowed to enter – officially – and come 1975 so too were men in wheelchairs. Women were allowed in wheelchairs a couple years after that.

The Boston Marathon is New England’s largest sporting event – 500,000 people come out to watch. What better way to celebrate Patriot’s Day, a particularly New England holiday marking the start of the Revolutionary War, than to watch people from around the world test their innate abilities against forces bigger than them? People run for charities and race in costumes watched by those in tri-corner hats and men in tights and buckle shoes, last seen seriously on the streets of the city in the end of the 18th Century. The race follows winding roads through the towns around Boston from the start in Hopkinton through Ashland, Framingham, Natick and Wellesley ending up in Copley Square by way of the Newton Hills, the most famous of which is known as Heartbreak Hill. It’s not even that steep, a mere 88 feet, but coming at miles 20-21, it marks a particular feat of endurance. By then you are spent and close to the wall. You have nothing left to give. And, the heartbreak for which it’s named isn’t just chest pain but the heartbreak of having to quit.

~

This morning I’m thinking of Joan Benoit Samuelson. I have no idea of her time or if she finished yesterday. But I keep thinking of her goal and her mettle. I want her to be the legacy of the marathon. Not bombs. Not violence. Not fear. Bravery and endurance. Pushing our boundaries.

I think too about what local hero Shalane Flanagan, making her debut yesterday in the race, said before the start: “I religiously watched the Boston Marathon and dreamed about what it would be like to run the course from Hopkinton to Boylston Street. I finally get the opportunity to fulfill my childhood dream and I can’t think of a better way to share this experience than with the community that raised me. In typical Boston style I know the love and support will be overwhelming.” The sentiment is a PR-worthy quote that now wears the weight of history.

I think of Clarence de Mar and also Greg Meyer who won the men’s race in 1983: “It’s hard to put into words what it means to win Boston. You can’t even dream that 30 years later that’s what people will remember…. It’s the strangest thing but it’s the power of the race. I don’t think Americans fully understand its power. If they did, they would dedicate more of their life to winning this.”

When the bombs went off, the race was three-quarters done. It was the four-hour mark. The big-name runners had long since crossed the finish line. Flanagan came in fourth, but still the crowd had remained cheering. They cheered for human effort, for defeating the odds, for the underdogs who remained to test their abilities, for everyone on the streets.