Tell me, why are we so blind to see? The ones we hurt are you and me.

Been spending most their lives living in a gangsta’s paradise.

Been spending most our lives living in a gangsta’s paradise.

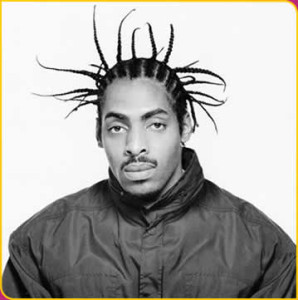

—Coolio “Gangsta’s Paradise”

The first purchase I made with my weekly allowance was the cassette single of Coolio’s Gangsta’s Paradise. It was the summer of 1998, and I was a 10-year-old white kid on a family vacation to Orlando, Florida. In the warm haze of favorite memories, I recall sitting in the beaming sun outside of Virgin Records, the insulating fuzz of my headphones secured over my ears, the Walkman whirring on my lap, the strings of the Stevie Wonder sample echoing in my empty head. As I listened to the song on loop, I never stopped to question who the hurt “you and me” of the chorus were, I only knew I loved the sound and the feeling however ineffable, that it elicited in me.

Now, 16 years later, it’s easy to note my naivety to the racial and economic differences that divide me, a white guy who grew up with family trips to Disney World, from the disenfranchised youths the song depicts – those that, as Coolio tells it, “have been blastin’ and laughin’ so long that/ even [their] momma think[s] that [their] mind is gone.” An adolescence spent avidly following the erosion of gangsta’ rap into the American mainstream has enlightened me to the cultural concerns that lie beneath my fandom: How can an outsider like myself truly appreciate a genre made by, and arguably for, a far-removed subculture? And what does this appreciation mean to the cycle that perpetuates the problems underlying the music? These questions supersede hip-hop; they’re intrinsic to America itself. They’re part of the thorny brush rooted along the muddy bank of the sprawling American mainstream, slowing the cultural coast’s erosion into the rushing torrent of appropriation.

Now, 16 years later, it’s easy to note my naivety to the racial and economic differences that divide me, a white guy who grew up with family trips to Disney World, from the disenfranchised youths the song depicts – those that, as Coolio tells it, “have been blastin’ and laughin’ so long that/ even [their] momma think[s] that [their] mind is gone.” An adolescence spent avidly following the erosion of gangsta’ rap into the American mainstream has enlightened me to the cultural concerns that lie beneath my fandom: How can an outsider like myself truly appreciate a genre made by, and arguably for, a far-removed subculture? And what does this appreciation mean to the cycle that perpetuates the problems underlying the music? These questions supersede hip-hop; they’re intrinsic to America itself. They’re part of the thorny brush rooted along the muddy bank of the sprawling American mainstream, slowing the cultural coast’s erosion into the rushing torrent of appropriation.

* * *

If I wasn’t in the rap game,

I’d probably have a key knee deep in the crack game.

Because the streets is a short stop –

Either you’re slinging crack rock or you got a wicked jump shot!

—Notorious B.I.G. “Things Done Changed”

There seem to be only two ways to escape the constraints of ghetto poverty: crime and commodification. This is the sad reality Christopher Wallace faced growing up as a poor black boy in Reagan-era Bed-Stuy. The dense horizon of housing projects provided few avenues of escape; the basic infrastructure needed to climb from such poverty seemed inaccessible, like rusted ladders without rungs. By 1992, when the 20-year-old Wallace stepped into the booth as Notorious B.I.G. to record his debut album, Ready To Die, he was fully aware of the limited opportunities afforded to him. How could he not be? He’d been born into a system designed to both marginalize and exploit those who inherit the burden of being both black and poor in America. As he saw it, he was limited to selling drugs, robbing people, playing sports, or making music. He started selling crack-cocaine in sixth-grade. By high school, the fast cash of street corner commerce overshadowed the dim allure of traditional schooling, so he dropped out at seventeen to be a full-time dealer. He was arrested three times in the following three years – another targeted statistic in the misguided War on Drugs. But he’d also always been a gifted orator, acing his English courses and killing competitors with street corner freestyles as a kid. He cartwheeled his criminal escapades into complicated rhythms of word play; his deep-voiced bursts of languidly spit lyrics were instantly marketable music. His first album netted him enough money to escape the poverty of his youth, but the violence inherent in his drug dealing past followed him into mainstream acclaim. The famous coastal feud that left the Bed-Stuy b-boy and his West Coast rival slain likely ignited the broadening appeal of the burgeoning genre. Music worth dying for is music begging to be heard.

There seem to be only two ways to escape the constraints of ghetto poverty: crime and commodification. This is the sad reality Christopher Wallace faced growing up as a poor black boy in Reagan-era Bed-Stuy. The dense horizon of housing projects provided few avenues of escape; the basic infrastructure needed to climb from such poverty seemed inaccessible, like rusted ladders without rungs. By 1992, when the 20-year-old Wallace stepped into the booth as Notorious B.I.G. to record his debut album, Ready To Die, he was fully aware of the limited opportunities afforded to him. How could he not be? He’d been born into a system designed to both marginalize and exploit those who inherit the burden of being both black and poor in America. As he saw it, he was limited to selling drugs, robbing people, playing sports, or making music. He started selling crack-cocaine in sixth-grade. By high school, the fast cash of street corner commerce overshadowed the dim allure of traditional schooling, so he dropped out at seventeen to be a full-time dealer. He was arrested three times in the following three years – another targeted statistic in the misguided War on Drugs. But he’d also always been a gifted orator, acing his English courses and killing competitors with street corner freestyles as a kid. He cartwheeled his criminal escapades into complicated rhythms of word play; his deep-voiced bursts of languidly spit lyrics were instantly marketable music. His first album netted him enough money to escape the poverty of his youth, but the violence inherent in his drug dealing past followed him into mainstream acclaim. The famous coastal feud that left the Bed-Stuy b-boy and his West Coast rival slain likely ignited the broadening appeal of the burgeoning genre. Music worth dying for is music begging to be heard.

The rise and demise of Christopher “Notorious B.I.G.” Wallace is an early indicator of what Harvard sociology professor Orlando Patterson calls “the Dionysian trap for young black men. The important thing to note about the subculture that ensnares them,” he writes in his 2006 op-ed for the New York Times, “is that it is not disconnected from the mainstream culture. To the contrary, it has powerful support from some of America’s largest corporations. Hip-hop, professional basketball and homeboy fashions are as American as cherry pie.” The same forces surrounding hip-hop that catapult rappers like Biggie from a life of crime to commercial success seem to reinforce the destructive context that fosters the music. His second album, Life After Death, released less than a week after his murder, sold more than 10 million copies – a Diamond-certified testament to the commercial value of hip-hop martyrdom.

* * *

Listen, Pops, want to know a little more about rap?

First rule: If it’s real it ain’t just a record deal,

It’s a trap!

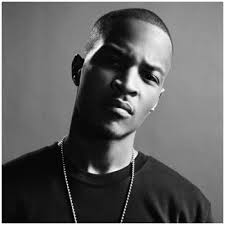

—T.I. “Trap Muzik”

By the early aughts, a decade after the release of Things Done Changed, the reality of growing up in the ghetto hadn’t improved. Though the torrent of mainstream music had swept a few people out of ghetto obscurity, the hierarchal system that perpetuates these ghettoes remained securely in place. Inner-city schools were still ineffective, drug laws still targeted the disenfranchised, and recidivism racked the ghetto in a brutal cycle. Hope exists as pinhole lights of rap dreams on the bleak ghetto horizon. Even those who managed to find riches through rap music are forced to straddle the drifting divide between commercial viability and the criminal life that provides their marketability. This is the trap that Clifford “T.I.” Harris discovered in his slide from Atlanta’s Bankhead streets into mainstream popularity, and the genre he dubbed “trap muzik” is the soundtrack of this Dionysian trap in action.

Though it’s impossible to compartmentalize such an amorphous and ever-evolving form as hip-hop for this essay, the “trap muzik” niche is uniquely focused on the idea of maintaining authenticity, of “keeping it real.” It’s a reaction to the continual erosion of gangster hip-hop into the mainstream. Like a drop of dye into water, hip-hop made an indelible impact upon its introduction. But as those initial drops dilute into the rushing waters of appropriation, as gangster rappers move from the margins into the mainstream, they drift further from the context that spurs their art. Superstar rappers like Jay Z have been elevated from drug dealing to art dealing, from a ghetto hell to a gangster’s paradise, while those still in the trap haven’t escaped the strictures of their subculture. The Roots drummer cum critic, Questlove, explores this phenomenon in the second installment of his “How Hip-Hop Failed Black America” series for Vulture:

“Hip-hop has become complicit in the process by which winners

are increasingly isolated from the populations they are supposed

to inspire and engage — which are also, in theory, the populations

that are supposed to furnish the next crop of winners.”

The rising affluence of hip-hop superstars intensifies the attitudes and ambitions of the ghetto’s youth who seek to replicate their extravagant wealth. But a trap rapper can’t forget the struggles that define his upbringing; the music is a reflection of that. The beats are generally dark and grimy orchestrations of heavy 808 bass, drill-line snares, and ominous strings; and the lyrics belligerent tales of the extreme highs and lows of the street life. School is shirked and drugs are sold, money is spent and people are shot. And the beat repeats.

The rising affluence of hip-hop superstars intensifies the attitudes and ambitions of the ghetto’s youth who seek to replicate their extravagant wealth. But a trap rapper can’t forget the struggles that define his upbringing; the music is a reflection of that. The beats are generally dark and grimy orchestrations of heavy 808 bass, drill-line snares, and ominous strings; and the lyrics belligerent tales of the extreme highs and lows of the street life. School is shirked and drugs are sold, money is spent and people are shot. And the beat repeats.

A trap rapper’s credibility is inextricable from his crimes; the drugs he sells to make the money he rains, the guns he wields to assert his strength, and the drugs he uses to dull the pain of his position are pillars of authenticity. On its surface, trap muzik seems to glorify these things, but it’s reductive to think that the music is solely an exaltation of them. Below the braggadocio lies institutional and cultural constrictions much greater and more complex than the music industry alone. Consider the context within which trap muzik is created, what more can be expected of its subject matter? T.I. explains as much in the closing lines of his 2003 song “Doin’ My Job”: “See, everything we know we learned from the streets/ Since 13 I’ve been hustling and earning my keep.” His survival, not just as a rapper, but also as a black kid in the ghetto, hinges on his hustle, and when the most rewarded hustle is a life of crime, then that is what’s pursued. Hip-hop history has shown how valuable a criminal background can be for a rap career, but the real-life repercussions of living and rapping about this lifestyle can prove ruinous to the messenger.

In T.I.’s introspective song “Still Ain’t Forgave Myself,” he opens the third verse with a run down of his criminal confidantes’s fates: “Out of all the niggas I was with when I was doing wrong, three in the fed, one doing life, and two dead and gone.” One would think that T.I. would recognize his fortune as the exception, and take his money and fly as far away from the street life as a private jet could take him. But that underestimates the black hole-like pull of the trap. In 2007, while on the way to the BET Awards show (where he had nine nominations and was set to perform), he made a stop in an Atlanta shopping-center parking lot to pick up $12,000 worth of guns he paid his bodyguard to buy for him. It was a sting – his trusted buyer turning on T.I. for a lessened sentence – and Clifford “T.I.” Harris was officially a two-time felon. Commercial success (his album from that year, T.I. VS T.I.P. went Platinum) and critical acclaim (he won two awards at the ceremony he missed) were not enough for the rapper to forget the past that propelled him to success. He’s “keeping it real,” even though his current reality as a mainstream rapper doesn’t necessitate the violent and self- destructive decisions he continues to make (see the tense stand-off he had with police in LA, or the brawl he started with professional boxer Floyd Mayweather in Las Vegas). The trap is too strong, and after all, he’s just doing his job.

* * *

And these is all my hood memories.

Since a little man I’ve been a G.

Tonight, if the Lord so happens to send for me,

Just cover me in Gucci – bury me a G.

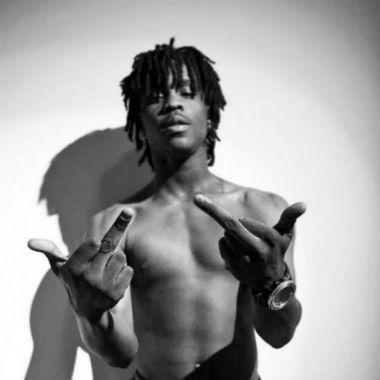

—Doe B “Hood Memories”

The specters of hip-hop’s fallen soldiers loom long and dark over the genre today. For every rapper that survives the trap, it seems two more are murdered trying. Tupac and Notorious B.I.G. are the obvious examples, but the list is devastatingly long: Houston’s Big Hawk and Fat Pat, Savannah’s Camouflague [sic], New Orleans’s Soulja Slim, New York’s Scott La Rock, Big L, and Jam Master Jay, Detroit’s Bugz and Proof… the list goes on ad nausem. But to continue the story of T.I., let’s focus on his late protégé Doe B, who was 22 when he was shot and killed at a bar in his (and my) hometown of Montgomery, Alabama.

Before he was Doe B the rapper, he was Glenn Thomas the trapper, selling weight to scrape by in southwest Montgomery. He’d faced the job’s inevitable violence in a shoot out in 2007. A Gucci-patterned eye-patch covered his bullet-damaged eye; a stylish signifier of his street credibility. Following the thorny trail from trapping to mainstream rapping seemed natural to Thomas, who naturally possessed a smooth, Deep South delivery of slurred syllables, Less than a year before his death, Doe B joined T.I.’s Grand Hustle Records, a move that poised him for commercial success. His stark, straightforward style hints at his nihilistic understanding of the blurred distinction between trapper and rapper. On “Mind of a Trapper” from his posthumous mixtape D.O.A.T. 3 (Definition of a Trapper), he raps: “Burglar bar doors on a brick house./ All this shit I sold I should be in a big house./ Don’t I put you in the mind of a trapper?” Here, he plays with the trap rappers dual role as criminal/entertainer: the “shit [he] sold” being either drugs or albums, the “big house” being a prison or a mansion. Experience shows how closely related the two are for those rappers in the trap, and Doe B, like Biggie and T.I. before him, knows it.

The mental state Doe B depicts is one of hopeless fatalism. On “Why,” from that same mixtape, he warbles in a slight auto-tune, “Lawd, when I die give me bullet proof wings./ And just cause I can fly these niggas wanna shoot me.” The lyrics hint at the same fear that urged T.I. to visit the parking-lot armory en route to the awards show. Success is a blaring target for jealous violence, and even in death, there’s no escape from the tentacles of the trap. The doom Doe B expected came for him on December 28, 2013. Authorities say two men entered the Centennial Hill Bar and Grill blasting AK-47’s in Doe B’s direction. Six were injured, another, a 21-year-old college girl, fell dead, and Doe B died on his way to the hospital. The street violence that inspired Doe B’s success in the studio spilled out of the speakers that night, affecting not only those that live and rap the trap life, but those that listen to it as well – a tragic reminder of the interconnectedness of trap rapper and fan.

The mental state Doe B depicts is one of hopeless fatalism. On “Why,” from that same mixtape, he warbles in a slight auto-tune, “Lawd, when I die give me bullet proof wings./ And just cause I can fly these niggas wanna shoot me.” The lyrics hint at the same fear that urged T.I. to visit the parking-lot armory en route to the awards show. Success is a blaring target for jealous violence, and even in death, there’s no escape from the tentacles of the trap. The doom Doe B expected came for him on December 28, 2013. Authorities say two men entered the Centennial Hill Bar and Grill blasting AK-47’s in Doe B’s direction. Six were injured, another, a 21-year-old college girl, fell dead, and Doe B died on his way to the hospital. The street violence that inspired Doe B’s success in the studio spilled out of the speakers that night, affecting not only those that live and rap the trap life, but those that listen to it as well – a tragic reminder of the interconnectedness of trap rapper and fan.

Though I grew up in the same small city as Doe B, our experiences there were dimensionally different. He lived in the city’s southwest side, a mostly destitute place abandoned by generations of white flight and redlining. My neighborhood, despite being only a few miles east of Doe B’s, is lined with white-pillared houses with two-car garages. Before dropping out, he went to an “apartheid high school” where 99% of its student body was black and more than 80% qualified for free lunch – one out of three students there failed to graduate. I attended a magnet high school where everyone graduated and nearly everyone continues to college. Doe B can structure whole verses off listing friends he’d lost to gun violence, while I doubt I know anyone who’s even been shot. And though I’m an avid fan of his music, I never visited the bar he frequented and performed at the day of his death. I was warded off by its earned reputation as a place where a shooting was all but inevitable. Admittedly, I was scared of the place. I can accept the violence in the abstract, in the movies I watch and the music I download, but not in the places I choose to visit. I grew up facing a bright and open horizon of financial and cultural opportunity, but with that privilege comes the responsibility to question its cost.

* * *

I know I’m finally rich, but ain’t a damn thing gonna change.

Me and my boys still bang, we’ll clap a nigga up, no range –

Bitch, I’m finally rich.

—Chief Keef “Finally Rich”

Trap muzik is an original product of the ghetto community, an outcry of the everyday struggles and minimal victories to which they’re limited. Record labels and music media exploit this situation – sensationalism sells. This conflict was recently inflamed by the 2012 release of trap rapper Chief Keef’s major label debut, Finally Rich. The album, full of harsh sounds and guttural grunts, is quintessential trap, and Keef, a troubled product of the infamous Southside Chicago projects, is the ultimate trapper. “Finally Rich,” was a critical success and a lightening rod of controversy. In January 2013, Pitchfork.tv took a 17-year- old Keef to a gun range for an interview to promote his new album. The rapper was on probation at the time for pointing a pistol at a Chicago police officer, and under investigation for involvement in the murder of rival Chicago rapper Lil JoJo. The video, showing him firing rifles and freestyling, violated that probation, sending him straight back to jail. But imprisonment is a promotional moment for a trap rapper, and Keef commemorates his freedom a few months later with a music video for his song “First Day Out”, capitalizing on his incarceration. Although Pitchfork apologized and removed the video that led to his arrest, the message is clear: play into our expectations of the violent ghetto kid and get a slap on the wrist and a bump in street cred.

This music seems to appeal equally (although differently) to white, middle-class listeners exempt from the ghetto restraints. A vast disparity exists between the realities of the privileged mainstream audience and those caught in the Dionysian trap. Resultant reactions of outsiderness and ownership flared up in the wake of Keef’s rise to mainstream acknowledgement. The New Republic’s David Bry explicates the album’s critical responses in his thinkpiece “Is it OK for White Music Critics to Like Violent Rap?”, citing the Twitter debate between then Spin critic Jordan Sargent (who is white), and Rap Radar editor Brian “B.dot” Miller (who is black).

B.Dot Miller’s calling people like Sargent (and myself) outsiders in hipster media echoes “the hipster” of Norman Mailer’s 1957 Dissent essay “The White Negro.” Through the essay’s rapturous drug-addled prose, Mailer attempts to explain his era’s fascination with jazz. The parallels between jazz and trap music show the cyclical nature of white appropriation of black culture, because, as Mailer writes (in the politically correct parlance of his time), “in this wedding of the white and the black it was the Negro that brought the cultural dowry.” For Mailer, the hipster is the American existentialist, one who understands the ever-present dangers of American modernity, “who [accepts] the terms of death, [lives] with death as immediate danger, [divorces] oneself from society, [exists] without roots, [and sets] out on that uncharted journey into the rebellious imperatives of the self.”

B.Dot Miller’s calling people like Sargent (and myself) outsiders in hipster media echoes “the hipster” of Norman Mailer’s 1957 Dissent essay “The White Negro.” Through the essay’s rapturous drug-addled prose, Mailer attempts to explain his era’s fascination with jazz. The parallels between jazz and trap music show the cyclical nature of white appropriation of black culture, because, as Mailer writes (in the politically correct parlance of his time), “in this wedding of the white and the black it was the Negro that brought the cultural dowry.” For Mailer, the hipster is the American existentialist, one who understands the ever-present dangers of American modernity, “who [accepts] the terms of death, [lives] with death as immediate danger, [divorces] oneself from society, [exists] without roots, [and sets] out on that uncharted journey into the rebellious imperatives of the self.”

Born into such fatalism, the ghetto’s black youth might be the lifeblood of the modern hip. The freewheeling spontaneity of jazz was hip’s manifestation in Mailer’s time – now that spirit sounds in trap music’s more explicit aggression. When he describes a black jazz musician giving “voice to the character and quality of his existence, to his rage and the infinite variations of joy, lust, languor, growl, cramp, pinch, scream and despair,” Mailer could very well be writing about the signature grumblings of Chief Keef, or the street reportage of Doe B.

Trap muzik may be the peephole into the ghetto black man’s existence, but to assume this relationship posits the outsider as voyeur is an issue to which Mailer seems oblivious. Mailer’s friend, the novelist James Baldwin, is quick to remind him of this problem. In “The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy,” a response to Mailer published in Esquire in 1961, Baldwin warns hipsters that “one does not become something else: one becomes nothing.” But the real fear, I think, is not in losing your identity; it’s in not being able to find a bit of yourself within another’s.

The outside forces that unwittingly encourage the genre’s trappings by listening to its music are inextricable from the insiders that make this music and live the life depicted within it. There’s really no separation of the cultures, it’s all part of the greater American culture of continual appropriation. The best trap music understands this connection, and that awareness gives the genre its value. We outsiders have a responsibility to analyze this music in order to understand the context that creates it. To dismiss the genre as dumb and destructive is to ignore the part of you that also exists in this margin between power and futility. “Too much is at stake for us to fail to understand the plight of these young men,” says Orlando Patterson. “For them, and for the rest of us.” If you still can’t believe us outsiders, then take it from T.I.’s lyrics on “Doin’ My Job”:

And for you to see what I’m saying, open eyes will help –

If you could think about somebody besides yourself.

Why you pointing fingers at me, analyze yourself.

Quit all that chastising and try to provide some help.

The only way to break the destructive cycle of the Dionysian trap is to first understand it, and the music that best reflects it is a good place to start.

I like what you guys are usually up too. This kind of clever work and coverage!

Keep up the very good works guys I’ve you guys to my blogroll.

This is really interesting, You are a very skilled blogger.

I have joined your feed and look forward to seeking

more of your magnificent post. Also, I’ve shared your website in my social networks!

When I originally commented I clicked the “Notify me when new comments are added”

checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get four emails with the same comment.

Is there any way you can remove people from that service?

Thanks a lot!

Good day! I know this is somewhat off topic but I

was wondering if you knew where I could get a captcha plugin for my comment

form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having trouble

finding one? Thanks a lot!

Hello, this weekend is nice designed for me, since this occasion i am reading this impressive

informative paragraph here at my residence.