HOLD ON TO your floppy-hatted academic regalia, folks, because I’m about to make a confession. As a faculty member in Columbia University’s Master’s Program in Narrative Medicine, I have been known to use (gasp!) trigger warnings in my undergraduate and graduate college classrooms.

But before you run screaming from your computer screen (“Oh, the humanity!”), let me explain. I know that the interwebs is all a-twitter with Trigger-gate: students at various U.S. campuses asking for trigger warnings on their syllabi. “Warning: The literary canon could make students squirm,” quips The New York Times. “Empathetically correct is the new politically correct,” sneers The Atlantic. “Trigger warnings on classic literature are one small step from book banning,” exclaims The Guardian. “I’m not putting a trigger warning on The Great Gatsby or Huckleberry Finn!” seems to be the overwhelming harrumph of college professors around the country. Those grumpy professorial declarations are then followed by the assertion that university classrooms should not be safe spaces, but spaces of intellectual challenge and controversy. (As if those two things are mutually exclusive?)

Although students from colleges including Oberlin, Rutgers, and UC Santa Barbara are asking for trigger warnings across their curricula, in not just literature classes but history, sociology, etc., the resounding objections to trigger warnings frame them as an assault on literature. Most public handwringing seems to be about how trigger warnings will destroy the Western canon itself. (This isn’t unlike how, whenever people critique the literary canon for its overwhelming whiteness, people always clutch at their pearls and cry, “but think of the children!”) To listen to these objections, one would imagine that America’s college campuses are populated entirely by helicopter-parented, whiney, privileged, and coddled brats who wilt like daisies at the mere mention of violence, sexism, racism, or bodily fluids in their classrooms.

~

At both Columbia and Sarah Lawrence College, I teach courses in everything from Illness and Disability Narratives; and Narrative, Health and Social Justice; to Fictions of Embodiment; and Diasporic Fiction. I teach film, memoir, short stories, and novels alongside sociological, anthropological, literary, disability, and trauma theory. My courses deals explicitly with issues like illness, disability, displacement, genocide, organ trafficking, racism, homophobia, and other traumas. I think deeply about secondary trauma and my students’ self care. I have been known to say “This is a difficult image,” or “There’s some pretty brutal stuff coming up in this week’s reading, guys,” before sharing gory or otherwise disturbing material. So, yes. I give my students bona fide trigger warnings.

But preventing little Johnny, José, or Jamila from getting a tad misty-eyed in a classroom is not, ideally, what trigger warnings are about. With their roots in the feminist blogosphere—where writers often want to give readers warnings before discussing explicit situations of sexual violence—trigger warnings in classrooms are about acknowledging that each student has her or his own specific life history, family context, identity, body—and that these realities have an impact on how a student understands and interacts with texts. (If I were being fancy, I might call this a type of reader-response theory.) To me, trigger warnings are also about recognizing structural power; that the personal overlaps with the academic; that reading, writing, and learning are political acts. In Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), Susan Sontag argued that, “Compassion is an unstable emotion. It needs to be translated into action, or it withers.” Overwhelming images of suffering can sometimes numb viewers—making them “bored, cynical, apathetic.” Trigger warnings, then, don’t just protect individual students; they are a possible way to circumvent this self-protective distancing, this feeling of “what can we do anyway?” that arises from being emotionally overwhelmed.

In my classes, I often suggest that students watch an assigned documentary together in a post-class viewing party. We leave time in class to discuss emotional as well as intellectual reactions. I have an online wiki-space on which students can discuss a reading or film before and after a class session. As a professor, I don’t dictate how my students should handle any distress they might feel, and I don’t excuse them from completing assignments. But I do often give them a heads up, suggesting they think through how they will support themselves and each other. And that’s all, ideally, a trigger warning is.

~

Then there’s the question of fiction vs. nonfiction—which, I’d argue, is a non-question, at least in my field. You may say that a documentary about the Rwandan genocide is different, from, say, a fictional account of violence in Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart; that the latter is only fiction and therefore somehow less affecting. I disagree. In fact, one of the principles of narrative medicine/medical humanities is that reading and writing narratives—both fiction and nonfiction—teaches future clinicians how to elicit, interpret, and act upon the narratives of their future patients. Reading the stories of Anton Chekov, Henry James, Toni Morrison, and Helena Maria Viramontes, helps equip doctors, nurses, therapists, and social workers with the intellectual and emotional fortitude to process and respond to suffering, trauma, illness, and loss. This is entirely because the lines between fictional representation and real life are not fixed boundaries, but porous, complex borderlands.

You may also say that using trigger warnings dictates to students how they should read (i.e.: view, interpret, understand) a film, essay or short story—by telling them I think it might be upsetting, I am not allowing them to make their own readerly judgements. And yes, that is the very real risk of such warnings. But to me, that risk is worth it. Let’s get real: none of us live in a vacuum. Just the mere title of a course, culture of a department, or nature of the professor’s previous teachings already influences the way students read texts. Anyway, as novelist Jay Caspian Kang asks in his meditation on trigger warnings in The New Yorker, “Why is the depersonalized, apolitical reading the one we should fight for?”

~

So does my use of trigger warnings in the classroom mean I think my students are weak? Not at all. Rather, it’s because I respect my students, and know that they all come with varied life experiences of which I know only a fraction. Who in my class has a brother who was killed in a homophobic attack? Who in my class survived a sexual assault last year, last month, last week? Who in my class fled their homeland as a result of ethnic cleansing? I don’t always know, but I do know that my students did not somehow hatch, fully grown, the moment they entered my class. Rather, they live complex lives outside of my classroom, lives which bring richness to our collective learning.

It was Brazilian educator Paolo Freire who, in his 1968 Pedagogy of the Oppressed, suggested that teachers not practice a banking model of education, assuming that truth is something that flows unidirectionally from professorial lips straight into the opened minds of students. Rather, learners bring their own rich and varied experiences to the classroom, experiences which must be honored and recognized. Learning then happens in collaboration between educators and students. In Teaching to Transgress (1994), bell hooks uses the term engaged pedagogy to describe a sort of education where teachers consider the whole contexts of their learners’ lives. In her words, “To teach in a manner that respects and cares for the souls of our students is essential if we are to provide the necessary conditions where learning can most deeply and intimately begin.”

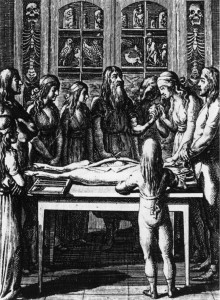

Anatomy in 1792. Engraving by Daniel Chodowiecki from Franz Heinrich Ziegenhagen, Lehre vom richtigen Verhältnis zu den Schöpfungswerken und die durch öffentliche Einführung desselben allein zu bewürkende algemeine Menschenbeglükkung

Caring for the souls of our students may seem a tall order, but recognizing that teaching is not a politically neutral activity is a start. Perhaps I am particularly sensitive to the varied needs of my varied students because my needs were so deeply ignored in my own graduate education. Since I am an MD and not a PhD, I know that medical school is environment where trigger warnings are unheard of, unless you’re talking about a nurse shouting when a crack dealer comes into the ER waving a loaded gun. I sat through lectures on melanoma interspersed with sexist slides of women in bikinis. I heard patients openly ridiculed by my superiors for their weight, smoking, or reproductive choices. I dissected dead bodies (a pretty darn emotionally upsetting activity). I put my own needs for sleep, food, and even using the bathroom secondary to learning patient care. All without trigger warnings. And yes, I survived.

But maybe we future doctors would have been better off had someone realized we were not robots, but real feeling human beings, whose emotional reactions had relevance to our future professional (and personal) lives. My program and other medical humanities programs like it all around the country were essentially created in order to address some of the damage done to clinicians by the traditional educational process. Treating clinical students badly creates doctors who treat their patients badly or, at least, are not taught to treat them well. Caring for our students’ emotional lives is a parallel process. By creating safe classrooms where students feel respected, cared for and educationally empowered, we lay a blueprint for future doctors who will respect, care for and empower their patients. And why can’t that same notion be applied to other students? Might treating this country’s future lawyers, politicians, parents, and yes, professors with intellectual respect and care create professionals who eventually approach their clients, constituents, children, and students with the same respect and care? I would suggest a resounding yes.

~

So am I arguing here that professors should be on the defensive, apologizing for introducing sensitive materials, or possibly bullied into not introducing those materials at all? No, no, and no. And certainly I, too, would resent any blanket regulation telling me that I must consider whether each and every text I teach might upset students in any teensy way.

But there is something important we educators can learn from Trigger-gate. These activist students who are urging professors to use trigger warnings on classroom texts may in fact be responding to a toxic educational culture—where campus rapes are de rigeur, where racist frat parties are still a dime a dozen, and where certain students feel intellectually welcome in classrooms, and others feel silenced. At heart, they may be simply asking us professors to pay attention to how structures of power work in our classrooms, and to help create safer learning environments—trigger warnings or no.

I actually agree with some trigger warning critics, who suggest that placing such responsibility on classroom professors may let university administrations off the hook from making sure that campuses are safe places, and that all students have disability, psychological counseling, and other services. I also agree that mandatory trigger warnings on syllabi open the door for students filing official complaints that may disproportionately target queer faculty, faculty of color, nontenured faculty, or faculty who are otherwise less powerful within a campus community.

But I still think that Trigger-gate is an opportunity, a chance for educators and learners to engage in a dialogue about the politics of education, and life, on our university campuses (and maybe join together to hold our respective university administrations to task). Maybe it is an opening to critique ourselves, and not only our students; a chance to recognize that, no matter the academic field, safety in the classroom isn’t antithetical to intellectual risk-taking and challenge; it is a prerequisite. These student-activists’ calls for trigger warnings is exactly what we educators should ideally want all our students to do: take responsibility for their education, and be pro-active agents rather than passive recipients of learning.

Is a uniform, mandated use of trigger warnings the answer? Of course not. But in limiting our reactions to Trigger-gate to simply that, we educators are perhaps asking entirely the wrong question.