LET’S NOT THROW out the baby with the bathwater

What will it take for this dreaded, haunted, innuendo-filled word to become a relic, a fossil, a member in good standing of the word museum?

I.

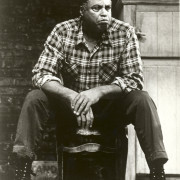

In August Wilson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play “Fences,” I heard James Earl Jones thunder the word over and over at the 46th Street Theater in New York in 1987. My sister and I sat in front of a vocal sistuh whose obnoxious commentary rattled us. At the climax, the garbage man Trey (Jones) brings home his outside baby to his long-suffering wife, his outside woman having died in childbirth. When Jones walked on, baby in his arms, the sistuh hollered, “Oh, no, he didn’t.” The great thespian James Earl Jones broke the fourth wall and glared at me. I felt like I could have clocked the sistuh, but that would’ve been pointless.

Wilson’s 28 uses of the N-word in “Fences” are anything but pointless. They are signifying of the highest order. Troy, the garbage man whose plight is the heart of the play, never addresses his wife Rose with it, only his sons and buddy Bono whom he met in prison. The volatile word doesn’t appear in the various work songs, secular chants and field hollers in the play. But Wilson opens the play with it:

BONO: Troy, you ought to stop that lying!

TROY: I ain’t lying! The nigger had a watermelon this big…. Talking about …” What watermelon, Mr. Rand?” I liked to fell out! “What watermelon, Mr. Rand?…And it sitting there big as life.

BONO: What did Mr. Rand say?

TROY: Ain’t said nothing. Figure if the nigger too dumb to know he carrying a watermelon, he wasn’t gonna get much sense out of him. Afraid to let the white man see him carry it home.

From the jump Troy is smart and knows it. A smart garbage man. A smart black garbage man in 1957. He uses the N-word repeatedly in camaraderie, where it is a term of endearment[“I love you, nigger”], gossip, history [“I done seen a hundred niggers play baseball better than Jackie Robinson.”], and definition by appositive [“If I had all the money niggers, these Negroes, throw away on numbers for one week-just one week-I’d be a rich man.”]. Bono only utters it twice, each time admonishing Troy about his hardheadedness.

In its final appearance in the play, the N-word holds intimacy and anonymity in the same breath. Troy kicks his son Cory him out of the house: “Nigger! That’s what you are. You just another nigger on the street to me!” The word is the blues, and Troy is the blues, a man who hates that he’s “been standing in the same place for eighteen years.” Devalued by Rose who agrees to raise the child but forsakes him [“From right now…this child got a mother. But you a womanless man”], Troy becomes a defeated man, the blues personified, what he called his son – “just another nigger on the street.”

Houston A. Baker Jr. defines Afro-American culture as a “complex, reflexive enterprise which finds its proper figuration in blues conceived of as matrix……a womb, a network…. Afro-American blues constitute such a vibrant network…They are the multiplex, enabling script in which Afro-American cultural discourse is inscribed.”

It is impossible to remove the N-word from this matrix, from the blues, from the vast “enabling script in which Afro-American cultural discourse is inscribed.” And one might as well confess, from American cultural discourse. Even if banished from conversation, one would have to 1) censor myriad texts from several centuries, 2) discard rap which, in itself, is providing a valuable history of Afro-American culture and discourse, and 3) perform mind control on millions of people.

While writing this essay, I saw “Fences” in Mill Valley, California, with actor Carl Lumbly [“Alias”] playing Troy. I’d forgotten how the play starts with that jocular N-word exchange between Troy and Bono. But Lumbly’s woebegone Troy thwarted the N-word’s nastiness. Instead I felt the loss of solace in Troy’s world, his diminution and slow death as the fence got built. Weeks later, I counted the number of times the word appeared in the play.

II.

I still use the N-word. I relish hearing it come out of my mouth in intimate conversation. My closest friends use the word around me. I have used it selectively around certain white friends (who don’t dare use it in my presence). I would like to say I don’t use it around strangers, children and babies. But I’ve used it around strangers in standup routines and later while reading my novel Virgin Soul across the country since March 2012. I’ve been taken aback by how harsh the N-word sounds when spoken aloud in a public library, how cool it sounds in a nightclub or a jazz setting, how petrifying it sounded at my local college library, where I could’ve heard a pin drop, none of the guffawing within the other relaxed environments (where drinks flow freely).

Virgin Soul took repeated drafts to get the novel right, and one complete draft to eliminate excessive use of the N-word which I couldn’t eliminate; Virgin Soul being historical fiction, the N-word at points lent authenticity. I self-censored because of the forced extinction and burial of the N-word with which I agree, in part. Used with the threat and/or act of murder, discrimination, prejudice, or brutality, of course the N-word is an abominable travesty. Used with affection between friends, in the height of lovemaking (yeah, people get freaky with it), when making an emphatic point in dialogue between podnahs, e.g. at a barbershop, on a street corner, at a family dinner with the O.G.s in the family a little toasted, the N-word is most appropriate.

I hate the commonality of white policemen using it against black men, hate that it has become extremely appropriate, meaning acceptable, expected and not even expounded upon by either party. I hate also that no one seems to recognize the enormously intimate relationship between white cops and black suspects (who often then become victims, convicts or recidivists). For hundreds of years now, this closeness, this Cain-and-Abel relationship, has flourished here in the United States. Nowhere else like it does here. We’ve permitted a special closeness between black men and armed white men in uniforms, whether they’re called police, National Guard, transit cops, prison guards or patrollers. Think of it. Who else can hit you about your head, limbs or torso, causing contusions, curse you, call you every name in the book including the N-word, and then tell you to call your lawyer? The only other person I’ve known who can get away with that is a husband. It is acceptable, expected and procedural. Oh, husbands can’t hit wives, you say. Police don’t abuse suspects, and reality is a rainbow. You wish. You can tell me to stop using the N-word all you want, but I never physically assault my friends when I use the word. I never beat them to the musical accompaniment of the N-word in two-beat chords. I’m very cordial and explanatory when I use the word, even anecdotally, with carefully chosen whites.

In teaching college literature for the past two decades, I’ve had two times when the N-word caused discomfort. The first occurred when my English literature class read aloud Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.” The protagonist in this short story, a grandmother traveling in 1940s Georgia, sees a backwoods black child whom she calls a “cute little pickaninny.” When her granddaughter sees he doesn’t even have pants on, the grandmother says, “[L]ittle niggers in the country don’t have the things we do.”

At this point, a black student got up and walked out of my class. She said she wouldn’t put up with black people being referred to this way. She never came back. This was midway through a 4-unit class, nothing to sneeze at. But the rest of the class had a lively discussion that day that brought out a lot of wisdom and understanding.

More recently, my English Lit class read aloud August Wilson’s “Fences” in a circle, a common technique for teaching plays. Three or four students read a scene, the next three or four students in the circle read the next scene, and so on, more random than casting for type. The day we read it, in a three-hour seminar, several students had a chance to read Troy’s lines. A white male student read Troy’s part, and class ended without time for a discussion. On the way home, I was perturbed. That last student reading a barrage of the N-word echoed in my head. His inflections sounded horrible, harsh and ugly, instead of familiar and affectionate. The next class I spoke about my reaction. We went back to the play and had several students of different races read the same lines with the N-word. The students agreed that the word sounded different but they hadn’t my extreme reaction. One explained that they knew the word sounded different when different kinds of people said it. They pretty much concluded that it sounded white and not intimate when spoken by one not so in tune with black culture, but defended each other’s attempt to capture August Wilson’s meaning, regardless of the N-word’s explosive possibility within the currency of the day.

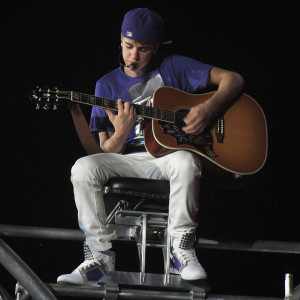

The first classroom incident upset a student but not me, the second upset me but not the students. Words can be landmines, lethal and dangerous, or simply signs that tell people what’s ahead. After its burial by the NAACP, its use by J-Lo that led to a proposed boycott, and its NFL ban, not to mention Justin Bieber’s tapes resurfacing this week, using the N-word in literature is even trickier than students discovering it in the canon. But it’s not impossible for this word to become a relic. Other words have become fossils, like malagrugorous (dismal) or jargogle (to confuse). People don’t twist their mouths to say these words because they’ve been in the word museum for centuries.

Long before the soulful acoustic guitar and tats, Bieber had the N-Word, cracking racist jokes as a teen.

Do we want to censor John Langston Gwaltney’s moving history of ordinary black people in his anthropological book Drylongso: A Self-Portrait of Black America because of the N-word?

“But if I show my black face in certain places, every cop in creation is right there.” “What is your business here?” “Keep moving, nigger.” “Do you work for some white family around here?” Shit, this might just as soon be South Africa.

If we cut the N-word here, as some want done to Huckleberry Finn, we remove the historical record of its use. If we censor comics using the word, we drive the impulse to say and hear it underground where it joins the black market (pun intended). It took me years to read Paul Lawrence Dunbar without disgust, and, similarly, old sayings like this:

White man got de money an’ education.

De Nigguh got Gawd an’ conjuration.

Was it the conflation of the N-word with dialect or my disgust which obscured the insight? “Gawd an’ conjuration” enabled black people to survive their holocaust.

III.

I’m actually not one to address my son with the N-word. Nor did my mother, a proper Oklahoman, ever use the word in direct address. But she quoted my grandmother, with relish, who forbade her daughters to party with “roundhouse niggers at the juke joint” in Muskogee, Oklahoma. My grandmother was steering posterity in the right direction. When my son began seeing a young woman with an adorable son while we (the village) were tending to his adorable son, I pulled on the blunter part of my grandma’s wisdom to make myself abundantly clear: “Son, we not raising yo’ baby while you go off and raise some other nigger’s baby. Let him raise his son and you raise yours.”

If brothers were in the audience at the Brainwash Café & Laundromat, a comedy spot in San Francisco, they would call out: “Do the black man fucking routine.” I could do it, i.e. use the N-word, because I was Troy Maxson talking to my homies. If it was mostly or only whites, using the N-word would have been degradation. Depending on how late it was, how raucous it was, how many blacks were there, I used the politically incorrect version. Call it the Dave Chappelle Syndrome. Dave quit his $50-mill gig when his comedy crossed the line between satire and self-abnegation.

[The politically incorrect version]

Nigguhs get ferocious when they fuck

Cuz nigguhs got to represent when they make love. They gotta represent their family, other black men, all your past lovers–they bring all that into the bed. So please do not attempt to fuck a bro – thuh on a futon. You see. Hollywood shows you how white men fuck ON TABLES & STAIRS & HARD SURFACES, ON DESKS & MARBLE STAIRCASES. Please!! This is not black men.

They need air bags underneath, not just mattresses. SPHLAT!! To fuck a black man, you need air bags, mattresses, foam, waterbeds, Sealy Posturepedic. And you best have a chiropractor in the next room. Nigguhs work at fucking. Some may say fuck work but they work hard at fucking.

Now, try the same routine with brothers, bro, or men in place of the N-word. It’s called censorship, another word for language manipulation. Controversial words stay alive and kicking because they have multiple meanings according to their use and their users. I’m not indifferent to arguments against the N-word. But I know, as a black person, that satirical comments and sarcasm about race are an intramural sport for black people. They offset the destructive and unrelenting racism that is the American way of life. Black writers, comics and social commentators get enormous mileage and ducats from acerbic satire. We will get to a post racist planet someday, maybe from a solar system where we can watch ourselves play with unkindness.

I heard a white TV actress say, “I feel vibratious.” I hope she was nervous and not just simple. When Dubya was the country’s father, he repeatedly said “nukaleer” instead of nuclear. He wasn’t impeached for that because it wasn’t a crime. Sarah Palin commits linguistic abomination every time she speaks. But because she doesn’t curse and looks like a 1950s Bess Myerson/Miss America, she’s indulged. I can hardly listen to Al Sharpton without calling up a friend to repeat his latest malapropism. I can’t act like the N-word is the worst crime against society. When it’s part of a crime, then it’s part of a crime. But when Weezy told George Jefferson on The Jeffersons, “Nigga, pullease,” that was as important as the signing of the Magna Carta. That was one for the books. The N-word can be horrible. It can be humorous. It has the duplicity of the f-word.

A terrible homicide in Oakland led me to write the prose poem I include here. I dare to satirize nigger in print because neither its commonplace use, uncommon power nor simple banishment will eradicate the cancer in race relations in this country. It’s not problem or solution; it’s an indication.

Bruno was from Brazil: a prose poem

“I’m from Oakland and I’m not a statistic. Yet. But New Year’s Eve I left the Bank of America at 2:30 pm; the news that night flashed on my bank. It was the scene of the last homicide of the year, at 3:20 pm.-, which meant I dodged a bullet by about 45 minutes. Witnesses say two Latino males and two African-American males had a parking lot altercation. The Latino driver used an ethnic slur and one of the black guys pulled out a gun and shot him. The two blacks drove off, witnesses say, and Bruno who was from Brazil and delivered pizza, for god’s sake, died on the spot…now you know the last word in the guidebook for new arrivals is nigger. Ask Camille Cosby. And I know poor, poor Bruno heard the word a thousand times delivering those pizzas. ‘Some nigguz on 90th Ave. want mushroom/salami/chicken…only nigguz want combos like that…you my nigga…when you get money from nigguz, check for counterfeit…nigguz, Bruno, watch out…’ Poor Bruno, the word probably came off his tongue like spit. And he didn’t know you could call a black person a nigger and get utter scorn and contempt. Like down South where they just ignored it and kept their inner dignity. But Bruno, you don’t call a real nigga a nigga. That’s like a death wish. Are you crazy? Suicidal? Certain words are like gods. They command respect. Nigger is a god. I’m so sorry for Bruno. He was a sacrificial lamb-that’s what you have to do with gods. You have to appease them, give em a lil’ somepin somepin. And I know Richard Pryor went to Africa after he made $50 million off the word and came back with religion. Stopped using the word and used crack instead. But he didn’t stop folks from using it. He just made the word an academic issue: shall we nigger; shall we not nigger? Forget Dick Gregory’s autobiography called Nigger. No, a Harvard law professor writes a book called Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word. Nigger is a God, nigger made millions, now it has a career. And the country’s leading black intellectual, a guy named Skippy, finds one of the first novels written by a black, titled, what else, Our Nig. So I’m proposing a constitutional amendment on the use of the word. There are simply days when it is dangerous to use the word. And one of those days is Friday night. And another of those days is Saturday night. Ok? On MLK’s birthday, abstain. Christmas, it goes without saying. The season is the reason. And proceed with caution on the Fourth of July. Fireworks, drinking and the use of the word by the wrong people don’t mix.”

NIGGA .PLEASE!

NIGGA .PLEASE! EMBRACE THE WORD NIGGA!

NIGGA PLEASE! EMBRACE THE WORD!

ONLY ANSWER TO WHAT YOU ARE! PEACE, LOVE AND SOUL.

Editor:

The following is from a personal note I sent to Judy; she asked me to post it in Weeklings. “Dialogue is priceless, especially when we’re calm”, she suggested. Judy and I are both playwrights and poets, and we have ended up over the years at a number of the same readings and other events, and I’m sure she agrees we could call ourselves “colleagues” if not “friends”. I admire her writing and her openness, and her intelligence, and decided to reply. Here is what I said: (I’ve added a few things in parenthesis if I thought my meaning might be unclear.)

Hi Judy,

The use of “nigger” is one custom I generally don’t discuss. I have two reasons:

One is I don’t use any of those ethnic slurs, “Jap”, Spick” and all that. They’re not intended to convey any real information about a person, so in the end, you don’t know what you’ve said and neither does anyone else. My family didn’t use them; my friends don’t use them; I never got used to them.

(I do make a literary/academic exception, for a classroom discussion or historic situation. I’ve used “nigger” in a play if my character would.)

The second reason is I usually bow out of a “nigger” discussion is that not only the word but the arguement itself seems to be intended to create separation. “It’s a black thang”. “You wouldn’t understand”. “You can’t even say it right!” (Ie, your opinion has no validity.) Fine, I won’t.

But I will mention to you that I think the Black treasuring of “nigger” is quite a bit like the boasting of how much abuse one took as a child, or how much one avoided “White” education: nothing more than a holdover from slavery. The way in which Blacks seem markedly different from other ethnic groups is the determination to hold on to customs of slavery! (Or whatever horrible way the group in question was forced to live/act.) Calling each other names, beating each other, the incredibly high rate of unmarried parenting.

One of my other Black friends says these things are nothing to do with slavery, because he remembers a time when these things were losing cachet. (Black) Kids wouldn’t dare skip school, etc., because their parents wouldn’t allow it.

But whatever the source of this word currently is, it seems sad and counterproductive and unlike everyone else for people to be calling their friends and family and fellow travelers something that is supposed to suggest the worst possible characteristics–whatever they are at the current time.

Judith O.

When we were unenlightened we called each other “Nigga”, “Nigguh”, sometimes proceeded with the word “black”; however we are an enlightened people and we KNOW that the underlying meaning of the word is degradation. It wasn’t a word we devised and called ourselves, no, it was a name given to us by the White Man! Therefore, anyway you slice it, you are slandering yourself. I personally hate the word, 9while I do understand the use in plays where it would have fit the time period). Rap may have started out using the word “Nigga” to press a point, but rap has been around more than 20 years and no longer needs to rely on the word to press or express a point. Everything evolves. We don’t call ourselves Negroes because ironically it connotes a Massa-Slave connection. So why call ourselves Niggas”?

Denigrating oneself will Not help you rise above and be PROUD.

I can’t stomach the idea of the word being used in an “affectionate” way–so many hundreds of thousands of people died having that word thrown at them every day, women hearing it in their ears while they were raped, children being called it instead of their own names while being told to perform a task. How could anyone be OK having it said to them or their loved ones? the meaning doesn’t change–use of that word replaces using the person’s name, eradicates their identity.