i.

HERE’S THE THING about clean-up hitters: they strike out a lot.

Then again, consider some of baseball’s most prodigious home run champions: Barry Bonds, Hank Aaron and Babe Ruth, the top three, had career batting averages of .298, .305 and .342, respectively. In baseball terms, excellent, but that also means they didn’t hit safely about sixty-to-seventy percent of the time they stepped to the plate. And these are the best of the best. Making a career at writing is not dissimilar to becoming a big league ball player: a hit every third attempt might enable you to remain employed, to call yourself a professional.

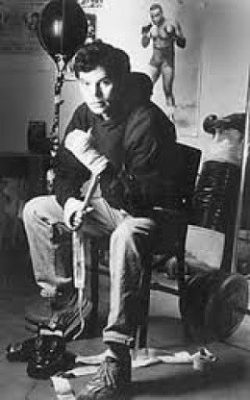

Thom Jones, in this umpire’s opinion, struck out a lot. He was a fast ball hitter, and when he saw a meatball down the middle, he could get hold of it. Epilepsy, punch-drunk boxers and wounded men battling addiction (to drugs, to drink, to bloodshed) comprised his sweet spot, and he returned to it often, albeit with increasingly diminished returns. When he stepped outside his comfort zone, the results could range from embarrassing to unreadable, and those moments occur with distressing frequency in his second (Cold Snap) and especially third (Sonny Liston Was a Friend of Mine) collections.

With very few exceptions, no honest (or sane) writer would quibble with a publishing history that confirms every third or fourth story is generally regarded as a home run, a minor classic, or even one worth remembering. Indeed, a great many writers would be perfectly content with every third or fourth story being an extra base hit. And then there are the thousands (millions?) of undiscovered writers who would trade years of their lives for a solitary single.

No sane or honest writer would ever want to be measured by their batting average of every published piece, over the course of a career.

You write often, as well as you can, and pray that, with a ton of practice and a little bit of luck, you manage to knock one clean out of the park. Mostly you just hope to make contact; to not strike out. Most of these failures, at least, don’t offend any audience; they languish—half-finished drafts, false starts and unattainable visions—in desk drawers or recycling bins.

Most writers, aware of the long odds and erratic whims of both publishers and potential readers, do their best to craft honest work that is more or less within the bounds of conventional taste, trusting the material is at once sufficiently unique and, for lack of a better word, straightforward. That’s to say, most writers (and it could be argued whether this applies more to obscure authors or established, even famous ones) are singles hitters. This is at once a function of the way publishing works (or doesn’t work—another topic altogether), and the internal battle most genuine writers wage that weighs originality vs. acceptance.

Note: I’m not talking about writing publishable work; writing that, for practical purposes, constitutes a single. I’m referring specifically to writers who, through ego or ability or ambition—or a combination of all three—set out to transcend cliché and write something unadulterated, that breaks some type of mold and becomes a new standard of sorts; something inimitable that itself will be emulated by future writers.

ii.

Thom Jones, like many famous writers, resists easy interpretation. A good chunk of his work is redundant, repurposed rather than convincing variations on a theme, and his penchant for stilted dialogue and ham-fisted histrionics mars some of his output. (Considering the publications he appeared in and the editors he worked with, it’s at once amusing and appalling to count the clichés throughout his three collections.) Another good chunk is serviceable, solid: a string of singles and the occasional double. He even hit a triple or two (These are recorded in Cold Snap; Sonny Liston Was a Friend of Mine is extremely tough going; taken on their own, the stories are underwhelming; compared to the previous collections they are somewhat excruciating…it can be debated that Jones burned out, lost his edge or, for any number of documented health reasons, couldn’t produce like he once did). But what separates him, and makes him worth celebrating, is that he had the audacity—and the skill—to make contact in historic fashion. We’re talking home runs like Carlton Fisk in ’75, Kirk Gibson in ’88 or Joe Carter with the walk-off World Series shot in ’93.

As it happens, all of these occur in his game-changing debut collection The Pugilist at Rest. A remarkable effort that deservingly became a National Book Award Finalist, it established Jones as a writer who, like Roy Hobbs, seemingly came out of nowhere, fully formed as a superstar. The title story’s publication is every writer’s dream; that one-in-a-billion fantasy: rescued from the slush pile and published by The New Yorker. That feat alone would more than satisfy most aspiring authors, but Jones, having alternately labored in obscurity and deferred his dream with years of substance abuse and self-sabotage, was ready for the big call-up. Unlike his next two books, there’s not a solitary stinker in the bunch. More significantly, of the eleven stories, (at least) six of them are no doubt dingers. Sabermetrically speaking, that’s well over .500, enough to ensure Jones legend status, one of the seminal debuts in the second-half of the 20th Century.

(To belabor the Hobbs metaphor, had Jones simply produced Pugilist, at 48, and then strode off into the sunset, he really might be considered the Wonderboy of short fiction.)

Opinions will—and should—vary, but in this critic’s estimation, six of these stories could be anthologized and might be studied by anyone hoping to ascertain what makes fiction memorable; what makes it resonate, what makes it work. The aforementioned title story, “Mosquitoes” and “Rocket Man” (allegedly Jones’s personal favorite) all clear the fence and will impart joy and delight (and envy) upon repeated readings.

With “A White Horse”, Jones manages to shoehorn Dostoyevsky, Hunter S. Thompson and the New Testament into a compressed tour de force—as well as any other story, this one best captures the outcast-in-search-of-epiphany. As a metaphor, the wealthy but unsettled protagonist shelling out hundreds to save a dying horse he encounters (à la Nietzsche) in the slums of Bombay seems at once familiar and surreal—Jones deftly combine pathos and desperation in the service of a postmodern parable, and cuts it (crucially) with humor.

Another masterpiece, and grand-slam, is the story of a dying woman entitled “I Want to Live!”. Older (but not that old), semi-estranged mother dying, alone, of cancer. Sound familiar? It’s to Jones’s considerable credit that he takes a potentially hackneyed subject that’s too often played for crocodile tear aesthetics, and deals, indelibly, with the heaviest—and trickiest—of issues: dread of death, longing for love, fear of a life wasted, et cetera.

Her friends came by. It was an effort to make small talk. How could they know? How could they know what it was like? They loved her, they said, with liquor on their breath. They had to get juiced before they could stand to come by! They came with casseroles and cleaned for her, but she had to sweat out her nights alone.

In less than thirty pages, Jones modernizes “The Death of Ivan Ilyich”, without the lugubrious sermonizing and melodrama Tolstoy, even at his best, struggled to suppress. It’s an unflinching, albeit harrowing tour of a helpless but not entirely hopeless woman’s death courtesy The Big C. In addition to merely working, as literature, it can console one with intimate experience with the disease, or prepare uninitiated readers for something too many families are forced to confront.

“The Black Lights”, a novel in miniature, could work as a longer piece (the writing is so unsullied, the characters so memorable, the recurring tension so concentrated), but illustrates the curious, often ineffable magic of the short form. There’s enough backstory related through flashback to provide a sense of who the narrator is, but the action occurs in the present, and we have no idea what the future holds, nor should we. In one of many astonishing passages, a Vietnam veteran stuck in a neuropsych ward to recover from his anxiety-induced epileptic seizures describes his first experience in a straitjacket (after driving the fellow patients to distraction with his paranoia that a large homicidal rabbit is lying in wait beneath his bed):

I forced myself to lie still, and it seemed that my brain was filled with sawdust and that centipedes, roaches, and other insects were crawling through it. I could taste brown rabbit fur in my teeth. I had a horror that the rabbit would come in the room, lie on my face, and suffocate me.

Finally released, months later, our anti-hero exits the base in one of the more memorable—and satisfying—endings of any modern short story. A bit of dialogue he exchanges with a fellow Marine typifies Jones, at the height of his powers:

“…You want to know something?”

“What’s that?”

“I stole this fucking car. Hot-wired the motherfucker.”

“Far out,” I said. “Which way you going?”

“As far as five bucks in gas will take me.”

“I got a little money. Drive me to Haight-Ashbury?”

“Groovy. What are you doing, man, picking your nose?”

“Just checking for cockroaches,” I said weakly.

This is a story that does everything the best writing aspires to do: it stays read, and changes the way you read, and understand, subsequent work. (In terms of Jones’s work, he arguably set the bar too high to approach that level again himself, but in the final analysis what matters is that he ever got there in the first place.)

iii.

To once again invoke Tolstoy, it could be said that all writers are unhappy, but each writer is unhappy in his or her own way.

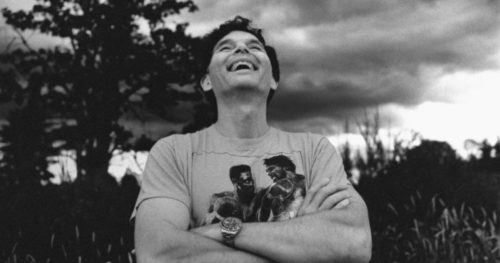

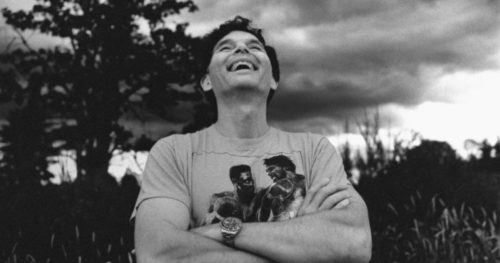

Thom Jones, by any benchmark, had a difficult life before, during and after The Pugilist at Rest was published (1993). An absent father who later committed suicide in a mental institution, Marine boot camp, boxing injuries resulting in epilepsy: these themes, which recur like grisly hallucinations in his fiction, all derived from his actual life. Indeed, by the time he was twenty, he’d already experienced the trauma and tragedy that would inform his best work.

Like Raymond Carver, Jones excels at depicting the seedier side of life, black and blue faces with blue collars as opposed to suits and suburban existential howling. Like Charles Bukowski, it’s not difficult to detect a clear line connecting the characters, situations and the person writing about them. Like Tim O’Brien, it’s not so much that his personal history serves as impetus but rather, the obsessions of memory, pain and regret are at once a unifying theme and creative cul-de-sac.

(Put another way, he was the anti-Updike; it is both refreshing and a little heroic that his work bulldogged its way into The New Yorker, unapologetic—but indubitably worthy—turds in that pristine literary punch bowl.)

Jones circled around these washed up palookas, chemically-altered outlaws and quiet nobodies in search of a rock to crawl under because he knew them; he was (or had been) one of them himself. His most compelling pieces seem unforced and unfettered because, while undeniably autobiographical, Jones used fiction as exploration, not therapy. In “The Pugilist at Rest”, the narrator invokes Theogenes, “the greatest of gladiators”, who fought—and won—fourteen hundred and twenty-five life and death battles. The statue commemorating this fighter (an image of which decorates the front cover) becomes the central metaphor not only for this story, but the entire collection. Indeed, the notion of a scarred and skillful brawler being called into the ring, yet again, to provide a spectacle, a distraction or voyeuristic pleasure, is an appropriate allegory for Jones’s career.

Jones once remarked that “in the act of writing I’m not Thom Jones. And it’s such a relief to not be Thom Jones.” How inspiring, how refreshing, how sad. It doesn’t seem a stretch to imagine that Jones had a strenuous life, even after 1993, and the inability to retain his title simply means he’s more Jake LaMotta and less Sugar Ray Robinson—not a one-shot wunderkind but a career scrapper who banged back at a world intent on beating the shit out of him. Whether or not he had a great deal more to write, the only fact that matters is that he took his one shot and made it count. Hopefully he redeemed a great deal of disillusionment with that triumph, but regardless, he had to know he’d escaped the most ignoble fate: obscurity.

His refusal to quit and unwillingness to sentimentalize his past is a testament to his character (that he didn’t need to sensationalize his past is testament to the extraordinary obstacles he overcame). That he plugged away, before and after he was famous, and that he turned his vocation into one long battle is a testament to his resolve, and artistic integrity. And while he wrote about manly men doing macho shit, Jones was the anti-Hollywood writer in the sense that he understood the sadness and futility of fighting, boozing, womanizing and hatred directed inward or outward. He learned how to write the way he learned how to survive: the hard way, with no short cuts and few excuses. His ability to craft unforgettable tales of otherwise forgettable people will endure as the ultimate testament to his distinct talent and warrior’s heart.

A dyed-in-the-wool music industry lifer, Brooks has carried amps for Pantera, played in punk bands up and down the West Coast, befriended the guys in Nirvana, shot music videos for the likes of Slayer, Eminem and the Melvins and he even directed William Shatner in a feature film. In recent years, Brooks earned the enduring love of Planet Earth’s heavy metal legions when he began directing episodes of Adult Swim’s late night comedy juggernaut, Metalocalypse, Brendon Small’s animated saga of a five-piece international death metal band and the secret international tribunal out to stomp them.

A dyed-in-the-wool music industry lifer, Brooks has carried amps for Pantera, played in punk bands up and down the West Coast, befriended the guys in Nirvana, shot music videos for the likes of Slayer, Eminem and the Melvins and he even directed William Shatner in a feature film. In recent years, Brooks earned the enduring love of Planet Earth’s heavy metal legions when he began directing episodes of Adult Swim’s late night comedy juggernaut, Metalocalypse, Brendon Small’s animated saga of a five-piece international death metal band and the secret international tribunal out to stomp them. Thanks to user-friendly software like GarageBand and ProTools, anybody can record an album in their bedroom and consequently we’re seeing an avalanche of self-produced albums flooding the Internet. We can deride the old model of gatekeepers all we want, but has this dilution of quality subverted the music business just as much as something like Napster?

Thanks to user-friendly software like GarageBand and ProTools, anybody can record an album in their bedroom and consequently we’re seeing an avalanche of self-produced albums flooding the Internet. We can deride the old model of gatekeepers all we want, but has this dilution of quality subverted the music business just as much as something like Napster? How does such a bright and energetic pop record absorb such darkness?

How does such a bright and energetic pop record absorb such darkness?